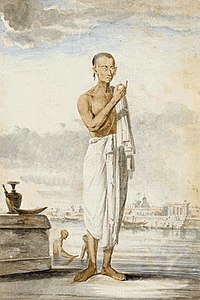

Bengali Brahmin

| Bengali Brahmins | |

|---|---|

A Bengali Brahmin priest | |

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages | Bengali |

| Populated states | West Bengal, India |

| Related groups | Maithil Brahmin, Utkala Brahmin, Kanyakubja Brahmin |

Bengali Brahmins are the community of Hindu Brahmins, who traditionally reside in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent, currently comprising the Indian state of West Bengal and the country of Bangladesh.

The Bengali Brahmins, along with Baidyas and Kayasthas, are regarded among the three traditional higher castes of Bengal.[1] In the colonial era, the Bhadraloks of Bengal were primarily, but not exclusively, drawn from these three castes, who continue to maintain a collective hegemony in West Bengal.[2][3][4]

History[edit]

Multiple land-grants to Brahmins, from since the Gupta Era have been observed.[5] The Dhanaidaha copper-plate inscription, dated to 433 CE, is the earliest of them and records a grantee Brahmin named Varahasvamin.[5] The 7th-century Nidhanpur copperplate inscription mentions that a marshy land tract adjacent to an existing settlement was given to more than 208 Vaidika Brahmins (Brahmins versed in the Vedas) belonging to 56 gotras and different Vedic schools.[6]

It is traditionally believed that much later, in the 11th century CE, after the decline of the Pala dynasty, a Hindu king, Adisura brought in five Brahmins from Kanauj, his purpose being to provide education for the Brahmins already in the area whom he thought to be ignorant, and revive traditional orthodox Brahminical Hinduism. As per tradition, these five immigrant Brahmins and their descendants went on to become the Kulin Brahmins.[7] According to Sengupta, multiple accounts of this legend exist, and historians generally consider this to be nothing more than myth or folklore lacking historical authenticity.[8] Identical stories of migration of Orissan Brahmins exist under the legendary king of Yayati Kesari.[9] According to Sayantani Pal, D.C Sircar opines that, the desideration of Bengali Brahmins to gain more prestige by connecting themselves with the Brahmins from the west, 'could have contributed' to the establishment of the system of 'kulinism'.[10]

Referring to the linkages between class and caste in Bengal, Bandyopadhyay mentions that the Brahmins, along with the other two upper castes, refrained from physical labour but controlled land, and as such represented "the three traditional higher castes of Bengal".[1]

Clans[edit]

Apart from the common classification as Kulina, Srotriya and Vamsaja, Bengali Brahmins are divided into the following clans or divisions:[11]

- Radhi

- Varendra

- Vaidika

- Saptasati

- Madhyasreni

- Sakadwipi

Post Partition of India[edit]

When the British left India in 1947, carving out separate nations, many Brahmins, whose original homes were in the newly created Islamic Republic of Pakistan, migrated en masse to be within the borders of the newly defined Republic of India, and continued to migrate for several decades thereafter to escape Islamist persecution.[12][13]

Notable people[edit]

- Raja Ganesha, founder of the Ganesha dynasty of Bengal

- Raja Krishnachandra Roy, Raja of Nadia Raj

- Rudranarayan, Maharaja of Bhurishrestha[14]

- Bhavashankari, Queen of Bhurishrestha[15]

- Rani Bhabani, Queen of Natore, kingdom of Rajshahi

- Abhijit Banerjee (born 1961), winner of the 2019 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences

- Surendranath Banerjee (1848–1925), founder of the Indian National Association, first Indian to pass the Indian civil service examination[16]

- Mahesh Chandra Nyayratna Bhattacharyya (1836–1906), Sanskrit scholar

- Bankim Chandra Chatterjee (1838-1894), Indian Bengali novelist, poet and journalist [17]

- Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1890–1977), linguist

- Sourav Ganguly (born 1972), President of BCCI and former captain of Indian National Cricket Team.

- Bagha Jatin (1879–1915), leader of the Jugantar party of revolutionary freedom fighters in Bengal

- Ashok Kumar (1911–2001), Indian film actor[18]

- Kishore Kumar (1929–1987), Indian playback singer, actor, music director, lyricist, writer, director, producer and screenwriter[18]

- Uttam Kumar (1926–1980), Indian Bengali actor

- Ashutosh Mukherjee (1864–1924), educator and barrister

- Pranab Mukherjee (1935–2020), 13th President of India and a veteran leader of the Indian National Congress[19]

- Syama Prasad Mukherjee (1901–1953), politician, barrister

- Hara Prasad Shastri (1853–1931), founder of the Charyapada.

- Dwarkanath Tagore (1794–1846), one of the first Indian industrialists to form an enterprise with British partners[20]

- Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941), poet who won the Nobel Prize in Literature

- Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (1820–1891), educator and social reformer

- M. N. Roy (1887–1954), Indian revolutionary, formed Communist party in India and Mexico

- Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833), social reformer

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004). Caste, Culture, and Hegemony: Social Dominance in Colonial Bengal. Sage Publications. p. 20. ISBN 81-7829-316-1.

- ↑ Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004). Caste, Culture, and Hegemony: Social Dominance in Colonial Bengal. Sage Publications. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-761-99849-5.

- ↑ Chakrabarti, Sumit (2017). "Space of Deprivation: The 19th Century Bengali Kerani in the Bhadrolok Milieu of Calcutta". Asian Journal of Social Science. 45 (1/2): 56. doi:10.1163/15685314-04501003. ISSN 1568-4849. JSTOR 44508277.

- ↑ Ghosh, Parimal (2016). What Happened to the Bhadralok?. Delhi: Primus Books. ISBN 9789384082994.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Griffiths, Arlo (2018). "Four More Gupta-period Copperplate Grants from Bengal". Pratna Samiksha: A Journal of Archaeology. New Series (9): 15–57.

- ↑ Shin, Jae-Eun (1 January 2018). Region Formed and Imagined: Reconsidering Temporal, Spatial and Social Context of Kāmarūpa, in Lipokmar Dzuvichu and Manjeet Baruah (eds), Modern Practices in North East India: History, Culture, Representation, London and New York: Routledge, 2018, pp.23-55

- ↑ Hopkins, Thomas J. (1989). "The Social and Religious Background for Transmission of Gaudiya Vaisnavism to the West". In Bromley, David G.; Shinn, Larry D. (eds.). Krishna consciousness in the West. Bucknell University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-8387-5144-2. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Sengupta, Nitish K. (2001). History of the Bengali-Speaking People. UBS Publishers' Distributors. p. 25. ISBN 81-7476-355-4.

- ↑ Witzel 1993, p. 267.

- ↑ Pal, Sayantani (2016), "Sena Empire", The Encyclopedia of Empire, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe043, ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4, retrieved 5 February 2022

- ↑ Saha, Sanghamitra (1998). A Handbook of West Bengal, Volume 1. International School of Dravidian Linguistics. pp. 53–54. ISBN 81-8569-224-6.

- ↑ "Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal". Time. 2 August 1971.

- ↑ Das, S. (1990). Communal Violence in Twentieth Century Colonial Bengal: An Analytical Framework. Social Scientist, 18(6/7), 21. doi:10.2307/3517477

- ↑ Bhattacharya, "Raybaghini o Bhurishrestha Rajkahini"

- ↑ Bhattacharya, "Raybaghini o Bhurishrestha Rajkahini"

- ↑ Dutt, Ajanta (6 July 2016). "Book review 'A Nation in Making': Banerjea's nation-A man and his history". The Asian Age. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ↑ Khan, Fatima (8 April 2019). "Bankim Chandra — the man who wrote Vande Mataram, capturing colonial India's imagination". The Print. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Kishore Kumar birthday: His favourite songs". India Today. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2020.

- ↑ "Protocol to keep President Pranab off Puja customs". Hindustan Times. 11 October 2011. Archived from the original on 31 August 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ↑ Littrup, Lisbeth (28 October 2013). Identity In Asian Literature. Routledge. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-136-10426-8.

References[edit]

- An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, by Damodar Dharmanand Kosāmbi, Popular Prakasan,35c Tadeo Road, Popular Press Building, Bombay-400034, First Edition: 1956, Revised Second Edition: 1975.

- Atul Sur, Banglar Samajik Itihas (Bengali), Calcutta, 1976

- NN Bhattacharyya, Bharatiya Jati Varna Pratha (Bengali), Calcutta, 1987

- RC Majumdar, Vangiya Kulashastra (Bengali), 2nd ed, Calcutta, 1989.

- Bhattacharya, Jogendra Nath (1896). Hindu Castes and Sects: An Exposition of the Origin of the Hindu Caste System and the Bearing of the Sects toward Each Other and toward Other Religious Systems. Calcutta: Thacker, Spink. p. iii.

- Dutta, K; Robinson, A (1995), Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-14030-4

- Siddiq, Mohammad Yusuf (2015). Epigraphy and Islamic Culture: Inscriptions of the Early Muslim Rulers of Bengal (1205–1494). Routledge. ISBN 9781317587460.

- Witzel, Michael (1993). "Toward a History of the Brahmins". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 113 (2): 264–268. doi:10.2307/603031. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 603031.