TikTok

| File:TikTok logo.svg | |

| Screenshot of TikTok.com homepage Screenshot of TikTok.com homepage | |

| Developer(s) | ByteDance |

|---|---|

| Initial release | September 2016 |

| Operating system | |

| Predecessor | musical.ly |

| Available in | 40 languages[1] |

List of languages

| |

| Type | Video sharing |

| License | Proprietary software with Terms of Use |

| Website | {{URL|example.com|optional display text}} |

| File:Douyin logo.svg | |

| Developer(s) | Beijing Microlive Vision Technology Co., Ltd |

|---|---|

| Initial release | 20 September 2016 |

| Operating system |

|

| Available in | 2 languages[2] |

List of languages | |

| Type | Video sharing |

| License | Proprietary software with Agreement |

| Website | douyin |

| Douyin |

|---|

TikTok, whose mainland Chinese counterpart is Douyin[3] (Chinese: 抖音; pinyin: Dǒuyīn), is a short-form video hosting service owned by ByteDance.[4] It hosts user-submitted videos, which can range in duration from 3 seconds to 10 minutes.[5]

Since their launches, TikTok and Douyin have gained global popularity.[6][7] In October 2020, TikTok surpassed 2 billion mobile downloads worldwide.[8][9][10] Morning Consult named TikTok the third-fastest growing brand of 2020, after Zoom and Peacock.[11] Cloudflare ranked TikTok the most popular website of 2021, surpassing Google.[12]

Corporate structure[edit]

ByteDance, based in Beijing, and its subsidiary TikTok Ltd were incorporated in the Cayman Islands. ByteDance is owned by its founders and Chinese investors (20%), other global investors (60%), and employees (20%).[13] TikTok Ltd owns four entities that are based respectively in the United States, Australia (which also runs the New Zealand business), United Kingdom (also owns subsidiaries in the European Union), and Singapore (owns operations in Southeast Asia and India).[14][15]

In April 2021, a state-owned enterprise owned by the Cyberspace Administration of China and China Media Group, the China Internet Investment Fund, purchased a 1% stake in ByteDance's main Chinese entity.[16][17][18][19][20] The Economist, Reuters, and Financial Times have described the Chinese government's stake as a golden share investment.[20][21][22]

Douyin[edit]

Douyin was launched by ByteDance in September 2016, originally under the name A.me, before rebranding to Douyin (抖音) in December 2016.[23][24] Douyin was developed in 200 days and within a year had 100 million users, with more than one billion videos viewed every day.[25][26]

While TikTok and Douyin share a similar user interface, the platforms operate separately.[27][3][28] Douyin includes an in-video search feature that can search by people's faces for more videos of them, along with other features such as buying, booking hotels, and making geo-tagged reviews.[29]

History[edit]

Evolution[edit]

ByteDance planned on Douyin expanding overseas. The founder of ByteDance, Zhang Yiming, stated that "China is home to only one-fifth of Internet users globally. If we don't expand on a global scale, we are bound to lose to peers eyeing the four-fifths. So, going global is a must."[30]

The app was launched as TikTok in the international market in September 2017.[31] On 23 January 2018, the TikTok app ranked first among free application downloads on app stores in Thailand and other countries.[32]

TikTok has been downloaded more than 130 million times in the United States and has reached 2 billion downloads worldwide,[33][34] according to data from mobile research firm Sensor Tower (those numbers exclude Android users in China).[35]

In the United States, celebrities, including Jimmy Fallon and Tony Hawk, began using the app in 2018.[36][37] Other celebrities, including Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Alba, Will Smith, and Justin Bieber joined TikTok as well as many others.[38]

In January 2019, TikTok allowed creators to embed merchandise sale links into their videos.[39]

On 3 September 2019, TikTok and the U.S. National Football League (NFL) announced a multi-year partnership.[40] The agreement occurred just two days before the NFL's 100th season kick-off at Soldier Field, where TikTok hosted activities for fans in honor of the deal. The partnership entails the launch of an official NFL TikTok account, which is to bring about new marketing opportunities such as sponsored videos and hashtag challenges. In July 2020, TikTok, excluding Douyin, reported close to 800 million monthly active users worldwide after less than four years of existence.[41]

In May 2021, TikTok appointed Shou Zi Chew as their new CEO[42] who assumed the position from interim CEO Vanessa Pappas, following the resignation of Kevin A. Mayer on 27 August 2020.[43][44][45]

In September 2021, TikTok reported that it had reached 1 billion users.[46] In 2021, TikTok earned $4 billion in advertising revenue.[47]

In October 2022, TikTok was reported to be planning an expansion into the e-commerce market in the US, following the launch of TikTok Shop in the United Kingdom. The company posted job listings for staff for a series of order fulfillment centers in the US and is reportedly planning to start the new live shopping business before the end of the year.[48]

According to data from app analytics group Sensor Tower, advertising on TikTok in the US grew by 11% in March 2023, with companies including Pepsi, DoorDash, Amazon and Apple among the top spenders. According to estimates from research group Insider Intelligence, TikTok is projected to generate $14.15 billion in revenue in 2023, up from $9.89 billion in 2022.[49]

Musical.ly merger[edit]

On 9 November 2017, TikTok's parent company, ByteDance, spent nearly $1 billion to purchase musical.ly, a startup headquartered in Shanghai with an overseas office in Santa Monica, California, U.S.[50][51] Musical.ly was a social media video platform that allowed users to create short lip-sync and comedy videos, initially released in August 2014. TikTok merged with musical.ly on 2 August 2018 with existing accounts and data consolidated into one app, keeping the title TikTok.[52] This ended musical.ly and made TikTok a worldwide app, excluding China, since China already had Douyin.[51][53][54]

Expansion in other markets[edit]

TikTok was downloaded over 104 million times on Apple's App Store during the first half of 2018, according to data provided to CNBC by Sensor Tower.[55]

After merging with musical.ly in August, downloads increased and TikTok became the most downloaded app in the U.S. in October 2018, which musical.ly had done once before.[56][57] In February 2019, TikTok, together with Douyin, hit one billion downloads globally, excluding Android installs in China.[58] In 2019, media outlets cited TikTok as the 7th-most-downloaded mobile app of the decade, from 2010 to 2019.[59] It was also the most-downloaded app on Apple's App Store in 2018 and 2019, surpassing Facebook, YouTube and Instagram.[60][61] In September 2020, a deal was confirmed between ByteDance and Oracle in which the latter will serve as a partner to provide cloud hosting,[62][63] as TikTok faces attempts to ban it in the United States.[64][65][66][67] In November 2020, TikTok signed a licensing deal with Sony Music.[68] In December 2020, Warner Music Group signed a licensing deal with TikTok.[69][70][71] In April 2021, Abu Dhabi's Department of Culture and Tourism partnered with TikTok to promote tourism.[72] It came following the January 2021 winter campaign, initiated through a partnership between the UAE Government Media Office partnered and TikTok to promote the country's tourism.[73]

Since 2014, the first non-gaming apps[74] with more than 3 billion downloads were Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Messenger; all owned by Meta. TikTok was the first non-Facebook app to reach that figure. Sensor Tower reported that although TikTok had been banned in India, its largest market, in June 2020, downloads in the rest of the world continue to increase, reaching 3 billion downloads in 2021.[75]

The advertising revenue of short video clips is lower than other social media: while users spend more time, American audience is monetized at a rate of $0.31 per hour, a third the rate of Facebook and a fifth the rate of Instagram, $67 per year while Instagram will make more than $200.[76]

TikTok works with Tehran Chamber of Commerce.[77]

Relationship with other tech platforms[edit]

Although the size of its user base falls short of that of Facebook, Instagram, or Youtube, TikTok reached 1 billion active monthly users faster than any of them.[78] Competition from TikTok prompted Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, to spend $120 million as of 2022 to entice more content creators to its Reels service, although engagement level remained low.[79] Snapchat had likewise paid out $250 million in 2021 to its creators.[80] Many platforms and services, including Youtube Shorts, began to imitate TikTok's format and recommendation page. Those changes caused a backlash from users of Instagram, Spotify, and Twitter.[78]

In March 2022, The Washington Post reported that Facebook's owner Meta Platforms paid Targeted Victory—a consulting firm backed by supporters of the U.S. Republican Party—to coordinate lobbying and media campaigns against TikTok and portray it as "a danger to American children and society." Its efforts included asking local reporters to serve as "back channels" of anti-TikTok messages, writing opinion articles and letters to the editor, including one in the name of a concerned parent, amplifying stories about TikTok trends, such as "devious licks" and "Slap a Teacher", that actually originated on Facebook, and promoting Facebook's own corporate initiatives. Ties to Meta were not disclosed to the other parties involved. Targeted Victory said that it is "proud of the work". A Meta spokesperson said that all platforms, including TikTok, should face scrutiny.[81]

The Wall Street Journal reported that Silicon Valley executives met with US lawmakers to build an "anti-China alliance" before TikTok CEO's Congressional hearing in March 2023.[82]

Features[edit]

The mobile app allows users to create short videos, which often feature music in the background and can be sped up, slowed down, or edited with a filter.[83] They can also add their own sound on top of the background music. To create a music video with the app, users can choose background music from a wide variety of music genres, edit with a filter and record a 15-second video with speed adjustments before uploading it to share with others on TikTok or other social platforms.[84]

The "For You" page on TikTok is a feed of videos that are recommended to users based on their activity on the app. Content is curated by TikTok's artificial intelligence depending on the content a user liked, interacted with, or searched. This is in contrast to other social networks' algorithms basing such content off of the user's relationships with other users and what they liked or interacted with.[85]

The app's "react" feature allows users to film their reaction to a specific video, over which it is placed in a small window that is movable around the screen.[86] Its "duet" feature allows users to film a video aside from another video.[87] The "duet" feature was another trademark of musical.ly. The duet feature is also only able to be used if both parties adjust the privacy settings.[88]

Videos that users do not want to post yet can be stored in their "drafts". The user is allowed to see their "drafts" and post when they find it fitting.[89] The app allows users to set their accounts as "private". When first downloading the app, the user's account is public by default. The user can change to private in their settings. Private content remains visible to TikTok but is blocked from TikTok users who the account holder has not authorized to view their content.[90] Users can choose whether any other user, or only their "friends", may interact with them through the app via comments, messages, or "react" or "duet" videos.[86] Users also can set specific videos to either "public", "friends only", or "private" regardless if the account is private or not.[90]

Users can also send their friends videos, emojis, and messages with direct messaging. TikTok has also included a feature to create a video based on the user's comments. Influencers often use the "live" feature. This feature is only available for those who have at least 1,000 followers and are over 16 years old. If over 18, the user's followers can send virtual "gifts" that can be later exchanged for money.[91][92]

TikTok announced a "family safety mode" in February 2020 for parents to be able to control their children's presence on the app. There is a screen time management option, restricted mode, and the option to put a limit on direct messages.[93][94] The app expanded its parental controls feature called "Family Pairing" in September 2020 to provide parents and guardians with educational resources to understand what children on TikTok are exposed to. Content for the feature was created in partnership with online safety nonprofit, Internet Matters.[95]

In October 2021, TikTok launched a test feature that allows users to directly tip certain creators. Accounts of users that are of age, have at least 100,000 followers and agree to the terms can activate a "Tip" button on their profile, which allows followers to tip any amount, starting from $1.[96]

In December 2021, TikTok started beta-testing Live Studio, a streaming software that would let users broadcast applications open on their computers, including games. The software also launched with support for mobile and PC streaming.[97] However, a few days later, users on Twitter discovered that the software uses code from the open-source OBS Studio. OBS made a statement saying that, under the GNU GPL version 2, TikTok has to make the code of Live Studio publicly available if it wants to use any code from OBS.[98]

In May 2022, TikTok announced TikTok Pulse, an ad revenue-sharing program. It covers the "top 4% of all videos on TikTok" and is only available to creators with more than 100,000 followers. If an eligible creator's video reaches the top 4%, they will receive a 50% share of the revenue from ads displayed with the video.[99]

In July 2023, TikTok launched a new streaming service called TikTok Music, currently available only in Brazil and Indonesia.[100] This service allows users to listen to, download and share songs.[100] It is reported that TikTok Music features songs from major record companies like Universal Music Group, Sony Music and Warner Music Group.[100] On 19 July 2023, TikTok Music was expanded for select users in Australia, Mexico and Singapore.[101]

Content and usage[edit]

Demographics[edit]

TikTok tends to appeal to younger users, as 41% of its users are between the ages of 16 and 24. These individuals are considered Generation Z.[85] Among these TikTok users, 90% said they used the app daily.[102] TikTok's geographical use has shown that 43% of new users are from India.[103] As of the first quarter of 2022, there were over 100 million monthly active users in the United States and 23 million in the UK. The average user, daily, was spending 1 hour and 25 minutes on the app and opening TikTok 17 times.[104]

By July 2023, TikTok has become the primary news source for British teenagers on social media, with 28% of 12 to 15-year-olds relying on the platform, while traditional sources like BBC One/Two are more trusted at 82%, according to a report by UK regulator Ofcom.[105]

Out of TikTok's top 100 male creators, a 2022 analysis reported 67% were white, with 54% having near-perfect facial symmetry.[106]

Popular TikTok users have lived collectively in collab houses, predominantly in the Los Angeles area.[107]

Teenage mode[edit]

China heavily regulates how Douyin is used by minors in the country, especially after 2018.[108] Under government pressure, ByteDance introduced parental controls and a "teenage mode" that shows only whitelisted content, such as knowledge sharing, and bans pranks, superstition, dance clubs, and pro-LGBT content.[lower-alpha 1][109] A mandatory screen time limit was put in place for users under the age of 14 and a requirement to link accounts to a real identity to prevent minors from lying about their age or using an adult's account. The differences between Douyin and TikTok have led some US politicians and commentators to accuse the company or the Chinese government of malicious intent.[108][110] In March 2023, TikTok announced default screen time limits for users under the age of 18. Those under the age of 13 would need a passcode from their parents to extend their time.[108]

Cyberbullying[edit]

Vox noted in 2018 that bullies and trolls were relatively rare on TikTok compared to other platforms.[111] Nonetheless, several users have reported cyberbullying via features such as Duet or React, which is used to interact with followers.[112] A trend making fun of autism eventually created a huge backlash, even on the platform itself, and the company ended up removing the hashtag altogether.[113][114] Parents filming how their children reacted to people with disability, often in terror, led to criticisms of ableism.[115] In December 2019, following a report by German digital rights group netzpolitik.org, TikTok admitted that it had suppressed videos by disabled users as well as LGBTQ+ users in a purported temporary effort to limit cyberbullying.[116][117]

Viral trends[edit]

Many recipes and food-related trends grew popular on TikTok, leading some content creators to gain millions of subscribers and the term "FoodTok" to be widely used. The amount of engagement on TikTok has encouraged more cooking in younger viewers and drawn in businesses from the food industry to market themselves on the platform and interact with followers.

The app has spawned numerous viral trends, Internet celebrities, and music trends around the world.[118] Duets, a feature that allows users to add their own video to an existing video with the original content's audio, have sparked many of these trends.[119] Many stars got their start on musical.ly, which merged with TikTok on 2 August 2018. These include Loren Gray, Baby Ariel, Zach King, Lisa and Lena, Jacob Sartorius, and many others. Loren Gray remained the most-followed individual on TikTok until Charli D'Amelio surpassed her on 25 March 2020. Gray's was the first TikTok account to reach 40 million followers on the platform. She was surpassed with 41.3 million followers. D'Amelio was the first to ever reach 50, 60, and 70 million followers. Charli D'Amelio remained the most-followed individual on the platform until she was surpassed by Khaby Lame on June 23, 2022. Other creators rose to fame after the platform merged with musical.ly on 2 August 2018.[120] TikTok also played a major part in making "Old Town Road" by Lil Nas X one of the biggest songs of 2019 and the longest-running number-one song in the history of the US Billboard Hot 100.[121][122][123]

TikTok has allowed many music artists to gain a wider audience, often including foreign fans. For example, despite never having toured in Asia, the band Fitz and the Tantrums developed a large following in South Korea following the widespread popularity of their 2016 song "HandClap" on the platform.[124] "Any Song" by R&B and rap artist Zico became number one on the Korean music charts due to the popularity of the #anysongchallenge, where users dance to the choreography of the song.[125] The platform has also launched many songs that failed to garner initial commercial success into sleeper hits, particularly since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic.[126][127] However, it has received criticism for not paying royalties to artists whose music is used on the platform.[128]

Classic stars are able to connect with younger audiences born decades after a musician's first debut and across traditional genres. In 2020 Fleetwood Mac's "Dreams" was used in a skating video and a recreation by Mick Fleetwood. The song re-entered Billboard Hot 100 after 43 years and topped Apple Music. In 2022, Kate Bush's "Running Up That Hill" went viral among fans of Stranger Things, topping the UK singles chart 37 years after its original release. In 2023 Kylie Minogue's "Padam Padam" entered the Radio 1 playlist after being shared by Gen Z, even though many youth radio stations had refused to play it. Other older artists with strong engagement on TikTok include Elton John and Rod Stewart.[129]

In June 2020, TikTok users and K-pop fans "claimed to have registered potentially hundreds of thousands of tickets" for President Trump's campaign rally in Tulsa through communication on TikTok,[130] contributing to "rows of empty seats"[131] at the event. Later, in October 2020, an organization called TikTok for Biden was created to support then-presidential candidate Joe Biden.[132] After the election, the organization was renamed to Gen-Z for Change.[133][134]

On 10 August 2020, Emily Jacobssen wrote and sang "Ode to Remy", a song praising the protagonist from Pixar's 2007 computer-animated film Ratatouille. The song rose to popularity when musician Daniel Mertzlufft composed a backing track to the song. In response, began creating a "crowdsourced" project called Ratatouille the Musical. Since Mertzlufft's video, many new elements including costume design, additional songs, and a playbill have been created.[135] On 1 January 2021, a full one-hour virtual presentation of Ratatouille the Musical premiered on TodayTix. It starred Titus Burgess as Remy, Wayne Brady as Django, Adam Lambert as Emile, Kevin Chamberlin as Gusteau, Andrew Barth Feldman as Linguini, Ashley Park as Colette, Priscilla Lopez as Mabel, Mary Testa as Skinner, and André De Shields as Ego.

A viral TikTok trend known as "devious licks" involves students vandalizing or stealing school property and posting videos of the action on the platform. The trend has led to increasing school vandalism and subsequent measures taken by some schools to prevent damage. Some students have been arrested for participating in the trend.[136][137] TikTok has taken measures to remove and prevent access to content displaying the trend.[138] Another TikTok trend known as the Kia Challenge involves users stealing certain models of Kia and Hyundai cars manufactured without immobilizers, which was a standard feature at the time, between 2010 and 2021.[139] As of February 2023, it had resulted in at least 14 crashes and eight deaths according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.[140] In May, Kia and Hyundai settled a $200-million class-action lawsuit by agreeing to provide software updates to affected vehicles and over 26,000 steering wheel locks.[141]

In 2023 a trend took off where streamers acted as if they were video-game characters following prompts from their viewers. Livestreaming as non-player characters or NPCs was already known in the cosplay community. It allows viewers to become more invested in their experience and creators to interact with their followers in real-time. When the trend exploded, some creators were able to make a living out of their performances. They believe that even if the trend does not last, it can supplement their income as they become better at content creation in general or pivot into other niches such as ASMR.[142]

On Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, some celebrities who had garnered large followings as of August 2019 include Dilraba Dilmurat, Angelababy, Luo Zhixiang, Ouyang Nana, and Pan Changjiang.[143] In the 2022 FIFA World Cup, a Qatari teenage royal became an Internet celebrity after his angry expressions were recorded in Qatar's opening match loss to Ecuador;[144] he amassed more than 15 million followers in less than a week after creating a Douyin account.[145]

Fashion and body size[edit]

"Midsize" fashion gained greater exposure on TikTok after many creators opened up about not able to find clothing sizes that fit them well. Women's apparel can roughly be divided into petite, straight, and plus sizes, leaving gaps in between. Realistic videos about how differently pieces of garment fit on a model compared to how they fit on a typical consumer resonated with many who had believed that they were alone in their struggle.[146][147][148]

Cosmetic surgery[edit]

Content promoting cosmetic surgery is popular on TikTok and has spawned several viral trends on the platform. In December 2021, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, the journal of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, published an article about the popularity of some plastic surgeons on TikTok. In the article, it was noted that plastic surgeons were some of the earliest adopters of social media in the medical field and many had been recognized as influencers on the platform. The article published stats about the most popular plastic surgeons on TikTok up to February 2021 and at the time, five different plastic surgeons had surpassed 1 million followers on the platform.[149][150]

In 2021, it was reported that a trend known as the #NoseJobCheck trend was going viral on TikTok. TikTok content creators used a specific audio on their videos while showing how their noses looked before and after having their rhinoplasty surgeries. By January 2021, the hashtag #nosejob had accumulated 1.6 billion views, #nosejobcheck had accumulated 1 billion views, and the audio used in the #NoseJobCheck trend had been used in 120,000 videos.[151] In 2020, Charli D'Amelio, the most-followed person on TikTok at the time, also made a #NoseJobCheck video to show the results of her surgery to repair her previously broken nose.[152]

In April 2022, NBC News reported that surgeons were giving influencers on the platform discounted or free cosmetic surgeries in order to advertise the procedures to their audiences. They also reported that facilities that offered these surgeries were also posting about them on TikTok. TikTok has banned the advertising of cosmetic surgeries on the platform but cosmetic surgeons are still able to reach large audiences using unpaid photo and video posts. NBC reported that videos using the hashtags '#plasticsurgery' and '#lipfiller' had amassed a combined 26 billion views on the platform.[153]

In December 2022, it was reported that a cosmetic surgery procedure known as buccal fat removal was going viral on the platform. The procedure involves surgically removing fat from the cheeks in order to give the face a slimmer and more chiseled appearance. Videos using hashtags related to buccal fat removal had collectively amassed over 180 million views. Some TikTok users criticized the trend for promoting an unobtainable beauty standard.[154][155][156]

Medication shortage[edit]

In November 2022, Australia's medical regulatory agency, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) reported that there was a global shortage of the diabetes medication Ozempic. According to the TGA, the rise in demand was caused by an increase in off-label prescription of the drug for weight loss purposes.[157] In December 2022, with the United States experiencing a shortage as well, it was reported that the huge increase in demand for the medicine was caused by a weight loss trend on TikTok, where videos about the drug exceeded 360 million views.[158][159][160] Wegovy, a drug that has been specifically approved for treating obesity, also became popular on the platform after Elon Musk credited it for helping him lose weight.[161][162]

Influencer marketing[edit]

TikTok has provided a platform for users to create content not only for fun but also for money. As the platform has grown significantly over the past few years, it has allowed companies to advertise and rapidly reach their intended demographic through influencer marketing.[163] The platform's AI algorithm also contributes to the influencer marketing potential, as it picks out content according to the user's preference.[164] Sponsored content is not as prevalent on the platform as it is on other social media apps, but brands and influencers still can make as much as they would if not more in comparison to other platforms.[164] Influencers on the platform who earn money through engagement, such as likes and comments, are referred to as "meme machines".[163]

In 2021, The New York Times reported that viral TikTok videos by young people relating the emotional impact of books on them, tagged with the label "BookTok", significantly drove sales of literature. Publishers were increasingly using the platform as a venue for influencer marketing.[165]

In December 2022, NBC News reported in a television segment that some TikTok and YouTube influencers were being given free and discounted cosmetic surgeries in order for them to advertise the surgeries to users of the platforms.[166]

In 2022, it was reported that a trend called "de-influencing" had become popular on the platform as a backlash to influencer marketing. TikTok creators participating in this trend made videos criticizing products promoted by influencers and asked their audiences not to buy products they did not need. However, some creators participating in the trend started promoting alternative products to their audiences and earning commission from sales made through their affiliate links in the same manner as the influencers they were originally criticizing.[167][168]

In June 2022, NBC News reported that some of the influencers paid by FeetFinder, a website that sells foot fetish content, did not disclose their videos were ads. FeetFinder said that it has suggested to influencers to be upfront about who was funding them. Existing sellers on FeetFinder said that the videos often misrepresented how "easy" it is to make money from posting feet pictures. Other TikTok creators have spoken out against accepting sponsorship deals indiscriminately and criticized those who posted undisclosed FeetFinder ads.[169]

Use by businesses[edit]

In October 2020, the e-commerce platform Shopify added TikTok to its portfolio of social media platforms, allowing online merchants to sell their products directly to consumers on TikTok.[170]

Some small businesses have used TikTok to advertise and to reach an audience wider than the geographical region they would normally serve. The viral response to many small business TikTok videos has been attributed to TikTok's algorithm, which shows content that viewers at large are drawn to, but which they are unlikely to actively search for (such as videos on unconventional types of businesses, like beekeeping and logging).[171]

In 2020, digital media companies such as Group Nine Media and Global used TikTok increasingly, focusing on tactics such as brokering partnerships with TikTok influencers and developing branded content campaigns.[172] Notable collaborations between larger brands and top TikTok influencers have included Chipotle's partnership with David Dobrik in May 2019[173] and Dunkin' Donuts' partnership with Charli D'Amelio in September 2020.[174]

Sex work[edit]

TikTok is regularly used by sex workers to promote pornographic content sold on platforms such as OnlyFans.[175] One porn actor posted a viral song referring to himself as an "accountant", starting a trend.[176] In 2020 TikTok updated their terms of service to ban content that promotes "premium sexual content", impacting a large number of adult content creators.[177] In response, they began substituting words in their captions and videos and using filters to censor explicit images. Evan Greer, director of Fight for the Future, believes that at some point, censorship becomes a fool's errand and we would never be "able to sanitize the Internet".[178][179] Some adult content creators have found a way to game TikTok's recommendation algorithm by posting riddles, which attract a large number of viewers trying and failing to solve them. Some of them are redirected to the creators' OnlyFans accounts and end up as subscribers there.[180]

STEM feed[edit]

In March 2023, TikTok introduced a dedicated feed for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) content. It works with Common Sense Networks to check for safety and age appropriateness and with the Poynter Institute for reliability of information.[181][182]

Heating[edit]

In January 2023, Forbes reported that a "heating" tool allows TikTok to manually promote certain videos, comprising 1-2% of daily views. The practice began as a way to grow and diversify content and influencers that were not automatically picked up by the recommendation algorithm. It was also used to promote brands, artists, and NGOs, such as the FIFA World Cup and Taylor Swift.[183] However, some employees have abused it to promote their own accounts or those of their spouses, while others have felt that their guidelines leave too much room for discretion. TikTok said only a few individuals can approve heating in the U.S. and the promoted videos take up less than 0.002% of user feeds. To address concerns of Chinese influence, the company is negotiating with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) such that future heating could only be performed by vetted security personnel in the U.S. and the process would be audited by third-parties such as Oracle.[184]

Censorship and moderation[edit]

TikTok's and Douyin's censorship policies have been criticized as non-transparent. Internal guidelines against the promotion of violence, separatism, and "demonization of countries" could be used to prohibit content related to the Tiananmen Square crackdown, Falun Gong, Tibet, Taiwan, Chechnya, Northern Ireland, the Cambodian genocide, the 1998 Indonesian riots, Kurdish nationalism, ethnic conflicts between blacks and whites, or between different Islamic sects. A more specific list banned criticisms against world leaders, including past and present ones from Russia, the United States, Japan, North and South Korea, India, Indonesia, and Turkey.[185][186] In 2019, TikTok took down a video about human rights abuses in the Xinjiang internment camps against Uyghurs but restored it after 50 minutes as well as the creator's account, saying that the action was a mistake and triggered by a brief "satirical" image of Osama bin Laden in another post.[187][188]

TikTok moderators were instructed to suppress posts from "For You" recommendations if the users shown were deemed "too ugly, poor, or disabled".[117][189] The consumption of alcohol, full or partial nudity, LGBT and intersex contents were restricted even in places where they are legal.[190] TikTok has since apologized and instituted a ban against anti-LGBTQ ideology, but censorship continues on Douyin due to regulations in China.[109][191] Douyin guidelines also forbid live broadcasting by unregistered foreigners, "feudal superstition", "money worship", smoking and drinking, competitive eating by the "already obese", "toxic" slime, "pornographic" ASMR such as ear-licking, and female anchors wearing revealing clothes.[186]

ByteDance said its early guidelines were global and aimed at reducing online harassment and divisiveness when its platforms were still growing. They have been replaced by versions customized by local teams for users in different regions.[192]

A March 2021 study by the Citizen Lab found that TikTok did not censor searches politically but was inconclusive about whether posts are.[3][193] A 2023 paper by the Internet Governance Project at Georgia Institute of Technology found no pro-China censorship on TikTok.[194]

Following increased scrutiny, TikTok said it is granting some outside experts access to the platform's anonymized data sets and protocols, including filters, keywords, criteria for heating, and source code.[195][196]

Extremism and hate[edit]

Concerns have been voiced regarding content relating to, and the promotion and spreading of hate speech and far-right extremism, such as antisemitism, racism, and xenophobia. Some videos were shown to expressly promote Holocaust denial and told viewers to take up arms and fight in the name of white supremacy and the swastika.[197] As TikTok has gained popularity among young children,[198] and the popularity of extremist and hateful content is growing, calls for tighter restrictions on their flexible boundaries have been made. TikTok has since released tougher parental controls to filter out inappropriate content and to ensure they can provide sufficient protection and security.[199]

In Malaysia, TikTok is used by some users to engage in hate speech against race and religion especially mentioning the 13 May incident after the 2022 election. TikTok responded by taking down videos with content that violated their community guidelines.[200]

In March 2023, The Jewish Chronicle reported that TikTok still hosted videos that promoted the neo-Nazi propaganda film Europa: The Last Battle, despite having been alerted to the issue four months prior. TikTok said it removed and would continue to remove the content and associated accounts and has blocked the search term as well.[201]

ISIL propaganda[edit]

In October 2019, TikTok removed about two dozen accounts that were responsible for posting ISIL propaganda and execution videos on the app.[202][203]

Misinformation[edit]

TikTok has banned Holocaust denial, but other conspiracy theories have become popular on the platform, such as Pizzagate and QAnon (two conspiracy theories popular among the U.S. alt-right) whose hashtags reached almost 80 million views and 50 million views respectively by June 2020.[204] The platform has also been used to spread misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic, such as clips from Plandemic.[204] TikTok removed some of these videos and has generally added links to accurate COVID-19 information on videos with tags related to the pandemic.[205]

In January 2020, left-leaning media watchdog Media Matters for America said that TikTok hosted misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic despite a recent policy against misinformation.[206] In April 2020, the government of India asked TikTok to remove users posting misinformation related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[207] There were also multiple conspiracy theories that the government is involved with the spread of the pandemic.[208] As a response to this, TikTok launched a feature to report content for misinformation.[209] It reported that in the second half of 2020, over 340,000 videos in the U.S. about election misinformation and 50,000 videos of COVID-19 misinformation were removed.[210]

To combat misinformation in the 2022 midterm election in the US, TikTok announced a midterms Elections Center available in-app to users in 40 different languages. TikTok partnered with the National Association of Secretaries of State to give accurate local information to users.[211]

In September 2022, NewsGuard Technologies reported that among the TikTok searches it had conducted and analyzed from the U.S., 19.4% surfaced misinformation such as questionable or harmful content about COVID-19 vaccines, homemade remedies, the 2020 US elections, the war in Ukraine, the Robb Elementary School shooting, and abortion. NewsGuard suggested that in contrast, results from Google were of higher quality.[212] Mashable's own test from Australia found innocuous results after searching for "getting my COVID vaccine" but suggestions such as "climate change is a myth" after typing in "climate change".[210]

Russian invasion of Ukraine[edit]

As of 2022, TikTok is the 10th most popular app in Russia.[213] After a new set of Russian fake news laws was installed in March 2022, the company announced a series of restrictions on Russian and non-Russian posts and livestreams.[214][215] Tracking Exposed, a user data rights group, learned of what was likely a technical glitch that became exploited by pro-Russia posters. It stated that although this and other loopholes were patched by TikTok before the end of March, the initial failure to correctly implement the restrictions, in addition to the effects from Kremlin's "fake news" laws, contributed to the formation of a "splInternet ... dominated by pro-war content" in Russia.[216][213] TikTok said that it had removed 204 accounts for swaying public opinion about the war while obscuring their origins and that its fact checkers had removed 41,191 videos for violating its misinformation policies.[217][218]

User privacy[edit]

Privacy concerns have also been brought up regarding the app.[219][220] In its privacy policy, TikTok lists that it collects usage information, IP addresses, a user's mobile carrier, unique device identifiers, keystroke patterns, and location data, among other data.[221][222]

In January 2020, Check Point Research discovered a vulnerability, later patched by TikTok, whereby a hacker could spoof TikTok's official SMS messages and replace them with malicious links to gain access to user accounts.[223]

In February, Reddit CEO Steve Huffman criticized the app, calling it "spyware".[224][225] TikTok said the accusations were made without evidence.[221]

In July, Wells Fargo banned the app from company devices due to privacy and security concerns.[226]

In August 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported that TikTok tracked Android user data, including MAC addresses and IMEIs, with a tactic in violation of Google's policies.[227][228] The report sparked calls in the U.S. Senate for the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to launch an investigation.[229]

A March 2021 study by the Citizen Lab found that TikTok did not collect data beyond the industry norms, what its policy stated, or without additional user permission.[193]

In June 2021, TikTok updated its privacy policy to include potential collection of biometric data, including "faceprints and voiceprints", for special effects and other purposes. The terms said that user authorization would be requested if local law demands such.[230] Experts considered the terms to be "vague" and their implications "problematic" in light of the general lack of robust data privacy laws in the United States.[231] Also in June, CNBC reported that according to former TikTok employees, some staff members in China and employees at ByteDance had access to US user data.[232]

In October 2021, following the Facebook Files and controversies about social media ethics, a bipartisan group of lawmakers also pressed TikTok, YouTube, and Snapchat on questions of data privacy and moderation for age-appropriate content. Lawmakers also "hammered" TikTok about whether consumer data could be turned over to Beijing through ByteDance, its parent company in China.[233] TikTok said it does not give information to China's government and "U.S. user data" is stored within the country with backups in Singapore. According to the company's representative, TikTok had "no affiliation" with the subsidiary Beijing ByteDance Technology, in which the Chinese government has a minority stake and board seat.[234]

In August 2022, software engineer and security researcher Felix Krause found that in-app browsers from TikTok and other platforms contained codes for keylogger functionality but did not have the means to further investigate whether any data was tracked or recorded. TikTok said that the code is disabled.[235]

In a November 2022 update to its European privacy policy, TikTok stated that its global corporate group employees from China and other countries could gain remote access to the user information of accounts from Europe based on "demonstrated need".[236]

In May 2023, The Wall Street Journal reported that former employees complained about TikTok tracking users who had viewed LGBT-related content, leading to fears of collected data potentially usable for blackmail.[237] It also reported that a former employee from 2018 was suing TikTok's parent, ByteDance, for wrongful termination from his job. The suit alleges that Hong Kong users' device information and communications were accessed by Chinese Communist Party members. ByteDance denied the claims and said the employee worked on a defunct project. The company pulled TikTok out of Hong Kong in 2020.[238]

In June 2023, TikTok confirmed that some financial information, such as tax forms and Social Security numbers, of American content creators are stored in China. This applies to those signing contracts with and receiving payment transactions from ByteDance. Whether similar information will remain exempt from being treated as "protected user data" is being negotiated with the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States.[239]

Underage users[edit]

As with other platforms popular with children, underage users may inadvertently reveal their daily routine and whereabouts, raising concerns of potential misuse by sexual predators.[240][241] At the time of reporting (2018), TikTok had only two privacy settings, either private or completely public, without any middle ground.[242] Comment sections of "sexy" videos, such as young girls dancing in revealing clothes, were found to contain requests for nude pictures. TikTok itself forbids direct messaging of videos and photos, which meant follow-up interactions, if any, would have to take place in some other form.[243][111]

On 22 January 2021, the Italian Data Protection Authority demanded that TikTok temporarily suspend Italian users whose age could not be established.[244] The order came after the death of a 10-year-old Sicilian girl involved in an Internet challenge. TikTok asked its users in Italy to confirm again that they were over 13 years old. By May, over 500,000 accounts had been removed for failing the age check.[245]

In July 2021, the Dutch Data Protection Authority fined TikTok €750,000 euros for offering privacy statements only in English but not in Dutch. It noted that TikTok had implemented positive measures, such as forbidding direct messaging for users younger than 16 and allowing their parents to manage privacy settings directly through a paired family account, but the risk of children pretending to be older when creating their account remains.[246][247]

TikTok raised the minimum age for livestreaming from 16 to 18 after a BBC News investigation found hundreds of accounts going live from Syrian refugee camps. 30 of them showed children begging for digital donation. TikTok reportedly took a 70% commission from some of them, a figure that the company disputed.[248]

Journalist spying scandal[edit]

In June 2022, BuzzFeed News reported that leaked audio recordings of internal TikTok meetings reveal employees in China had access to overseas data, including a "master admin" who could see "everything". Some of the recordings were made during consultations with Booz Allen Hamilton, a US government contractor. A spokesperson of the contractor said some of the report's information was inaccurate but would neither confirm nor deny whether TikTok was one of its clients.[249] Following the reports, TikTok confirmed that employees in China could have access to U.S. data.[250] It also announced that US user traffic would now be routed through Oracle Cloud and that backup copies would be deleted from other servers.[251]

In October 2022, Forbes reported that a team at ByteDance planned to surveil certain US citizens for undisclosed reasons. TikTok said that the tracking method suggested by the report would not be feasible because precise GPS information is not collected by the platform.[252][253] In December 2022, ByteDance confirmed after internal investigation that the data of two journalists and their close contacts had been accessed by its employees from China and the United States on an "audit" team. The audit was intended to uncover sources of leaks who might have met with the journalists from Forbes and the Financial Times. The data accessed included IP addresses, which can be used to approximate a user's location. Four employees have been terminated, including the audit team's lead Chris Lepitak and his superior, executive Song Ye. ByteDance and TikTok condemned the individuals' misuse of authority.[254] The incident is being investigated by the US Department of Justice and FBI.[255][256][257] The US Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia reportedly subpoenaed information from ByteDance regarding efforts made to access US journalists' private user data using TikTok.[258]

European data privacy investigations[edit]

In September 2021, the Ireland Data Protection Commission (DPC) launched investigations into TikTok concerning the protection of minors' data and transfers of personal data to China.[259][260] The Irish DPC became the lead agency to handle such matters after TikTok established an office in the country, taking over investigations started by Dutch and Italian authorities.[261][246]

Project Clover[edit]

TikTok has faced criticism for transfering European user data to servers in the United States. It is holding discussions with UK's National Cyber Security Centre about a "Project Clover" for storing European information locally. The company plans to build two data centers in Ireland and one more in Norway. A third party will oversee the cybersecurity policies, data flows, and personnel access independently of TikTok.[262][263][13]

UK Information Commissioner's Office investigation[edit]

In February 2019, the United Kingdom's Information Commissioner's Office launched an investigation of TikTok following the fine ByteDance received from the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC). Speaking to a parliamentary committee, Information Commissioner Elizabeth Denham said that the investigation focuses on the issues of private data collection, the kind of videos collected and shared by children online, as well as the platform's open messaging system which allows any adult to message any child. She noted that the company was potentially violating the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) which requires the company to provide different services and different protections for children.[264]

Privacy Commissioner of Canada investigation[edit]

In February 2023, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, along with its counterparts in Alberta, British Columbia, and Quebec, launched an investigation into TikTok's data collection practices.[265]

Texas Attorney General investigation[edit]

In February 2022, the incumbent Texas Attorney General, Ken Paxton, initiated an investigation into TikTok for alleged violations of children's privacy and facilitation of human trafficking.[266][267] Paxton claimed that the Texas Department of Public Safety gathered several pieces of content showing the attempted recruitment of teenagers to smuggle people or goods across the Mexico–United States border. He claimed the evidence may prove the company's involvement in "human smuggling, sex trafficking and drug trafficking." The company claimed that no illegal activity of any kind is supported on the platform.[268]

U.S. COPPA fines[edit]

On 27 February 2019, the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) fined ByteDance U.S.$5.7 million for collecting information from minors under the age of 13 in violation of the Children's Online Privacy Protection Act.[269] ByteDance responded by adding a kids-only mode to TikTok which blocks the upload of videos, the building of user profiles, direct messaging, and commenting on others' videos, while still allowing the viewing and recording of content.[270] In May 2020, an advocacy group filed a complaint with the FTC saying that TikTok had violated the terms of the February 2019 consent decree, which sparked subsequent Congressional calls for a renewed FTC investigation.[271][272][273][274] In July 2020, it was reported that the FTC and the United States Department of Justice had initiated investigations.[275]

Addiction and mental health concerns[edit]

There are concerns that some users may find it hard to stop using TikTok.[276] In April 2018, an addiction-reduction feature was added to Douyin.[276] This encouraged users to take a break every 90 minutes.[276] Later in 2018, the feature was rolled out to the TikTok app. TikTok uses some top influencers such as Gabe Erwin, Alan Chikin Chow, James Henry, and Cosette Rinab to encourage viewers to stop using the app and take a break.[277]

Many were also concerned with the app affecting users' attention spans due to the short-form nature of the content. This is a concern as many of TikTok's audience are younger children, whose brains are still developing.[278] TikTok executives and representatives have noted and made aware to advertisers on the platform that users have poor attention spans. With a large amount of video content, nearly 50% of users find it stressful to watch a video longer than a minute and a third of users watch videos at double speed.[104] TikTok has also received criticism for enabling children to purchase coins which they can send to other users.[279]

In February 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that "Mental-health professionals around the country are growing increasingly concerned about the effects on teen girls of posting sexualized TikTok videos."[280] In March 2022, a coalition of U.S. state attorneys general launched an investigation into TikTok's effect on children's mental health.[281] In June 2022, TikTok introduced the ability to set a maximum uninterrupted screen time allowance, after which the app blocks off the ability to navigate the feed. The block only lifts after the app is exited and left unused for a set period of time. Additionally, the app features a dashboard with statistics on how often the app is opened, how much time is spent browsing it and when the browsing occurs.[282]

Since 2021, it has been reported that accounts engaging with contents related to suicide, self-harm, or eating disorder were fed more of similar videos. Some users were able to circumvent TikTok filters by writing in code or using unconventional spelling. The company has faced multiple lawsuits pertaining to wrongful deaths. TikTok said it is working to break up these "rabbit holes" of similar recommendations. US searches for eating disorder receive a prompt that offers mental health resources.[283][284][285]

In 2021, the platform revealed that it will be introducing a feature that will prevent teenagers from receiving notifications past their bedtime. The company will no longer send push notifications after 9 PM to users aged between 13 and 15. For 16 to 17 year olds, notifications will not be sent after 10 PM.[286] In March 2023, TikTok announced default screen time limits for users under the age of 18. Those under the age of 13 would need a passcode from their parents to extend their time.[287]

The Wall Street Journal has reported that doctors experienced a surge in reported cases of tics, tied to an increasing number of TikTok videos from content creators with Tourette syndrome. Doctors suggested that the cause may be a social one as users who consumed content showcasing various tics would sometimes develop tics of their own,[288] akin to mass psychogenic illness.[289][290]

Workplace conditions[edit]

Several former employees of the company have claimed of poor workplace conditions, including the start of the workweek on Sunday to cooperate with Chinese timezones and excessive workload. Employees claimed they averaged 85 hours of meetings per week and would frequently stay up all night in order to complete tasks. Some employees claimed the workplace's schedule operated similarly to the 996 schedule. The company has a stated policy of working from 10 AM to 7 PM five days per week (63 hours per week), but employees noted that it was encouraged for employees to work after hours. One female worker complained that the company did not allow her adequate time to change her feminine hygiene product because of back-to-back meetings. Another employee noted that working at the company caused her to seek marriage therapy and lose an unhealthy amount of weight.[291] In response to the allegations, the company noted that they were committed to allowing employees "support and flexibility".[292][293]

Bans and attempted bans[edit]

Asia[edit]

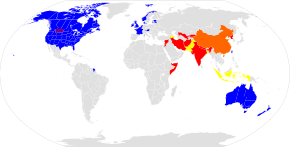

As of January 2023[update], TikTok is reportedly banned in several Asian countries including Afghanistan,[294] Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh,[295][296] India,[297][298][299] Iran,[300] Pakistan,[301] and Syria. The app was previously banned temporarily in Indonesia[302] and Jordan,[303] though both have been lifted since.

With reports that Palestinians resorted to TikTok for promoting their cause after platforms like Facebook and Twitter blocked their content,[304] Israeli analyst Yoni Ben-Menachem told Arab News in 2022 that the Chinese app was a "tool of dangerous influence" inciting violence through videos glorifying attacks against Israelis.[305][306] The Palestinian militant group Lion's Den gained much of their popularity through TikTok, according to Ynet.[307] In February 2023, Otzma Yehudit politician Almog Cohen advocated blocking TikTok for all of East Jerusalem.[308]

Canada[edit]

In February 2023, the Canadian government banned TikTok from all government-issued mobile devices.[309]

Europe[edit]

In February 2023, the European Commission and European Council banned TikTok from official devices.[310][311]

Belgium[edit]

In March 2023, Belgium banned TikTok from all federal government work devices over cybersecurity, privacy, and misinformation concerns.[312]

Denmark[edit]

In March 2023, Denmark's Ministry of Defence banned TikTok on work devices.[313]

France[edit]

In July 2023, members of the French parliament recommended a general ban of TikTok unless it were to "come clean". Concerns ranged from the company's ownership structure, the effectiveness of the app's content moderation and age limits. Government officials also blamed TikTok and other social media platforms for the riots that ensued after the police shooting of Nahel Merzouk. The recommendation was non-binding.[314]

United Kingdom[edit]

In March 2023, the UK government announced that TikTok would be banned on work devices used by ministers and other employees, amid security concerns relating to the app's handling of user data. Downing Street and the Ministry of Defence can continue to use the app under some exempting circumstances.[315] The same month, the BBC told all employees to delete TikTok off their devices unless the app was being used for work purposes. The network is also reportedly considering a ban on the app.[316]

United States[edit]

In January 2020, the United States Army and Navy banned TikTok on government devices after the Defense Department labeled it a security risk. Before the policy change, army recruiters had been using the platform to attract young people. Unofficial promotional videos continue to be posted on TikTok under personal accounts, drawing the ire of government officials, but they have also helped boost the number of enlistees; several accounts have millions of views and followers.[317][318][319]

According to a 2020 article in The New York Times, CIA analysts determined that while it is possible the Chinese government could obtain user information from the app, there was no evidence it had done so.[320] Several independent cybersecurity experts have also concluded that there is no determinable evidence that user information was being or had been obtained by the Chinese government, although they note that the amount of data that the app collects is of comparable volume to other social media apps, including U.S.-based platforms such as Facebook and Twitter.[321][322]

On 6 August 2020, then U.S. President Donald Trump signed an order[323][324] which would ban TikTok transactions in 45 days if it was not sold by ByteDance. Trump also signed a similar order against the WeChat application owned by the Chinese multinational company Tencent.[325][326]

On 14 August 2020, Trump issued another order[327][328] giving ByteDance 90 days to sell or spin off its U.S. TikTok business.[329] In the order, Trump said that there is "credible evidence" that leads him to believe that ByteDance "might take action that threatens to impair the national security of the United States."[330] Donald Trump was concerned about TikTok being a threat because TikTok's parent company was rumored to be taking United States user data and reporting it back to Chinese operations through the company ByteDance.[331]

In June 2021, new president Joe Biden signed an executive order revoking the Trump administration ban on TikTok, and instead ordered the Secretary of Commerce to investigate the app to determine if it poses a threat to U.S. national security.[332]

In June 2022, FCC Commissioner Brendan Carr called for Google and Apple to remove TikTok from their app stores, citing national security concerns, saying TikTok "harvests swaths of sensitive data that new reports show are being accessed in Beijing."[333][334]

In September 2022, during a testimony to the Senate Homeland Security Committee, TikTok's COO would not commit to stopping "all data and metadata flows" to China. The COO reacted to concerns of the company's handling of user data by stating that TikTok does not operate in China, though the company does have an office there.[335]

In November 2022, Christopher A. Wray, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, told U.S. lawmakers that "the Chinese government could use [TikTok] to control data collection on millions of users or control the recommendation algorithm, which could be used for influence operations."[336]

In December 2022, Senator Marco Rubio and representatives Mike Gallagher and Raja Krishnamoorthi introduced the Averting the National Threat of Internet Surveillance, Oppressive Censorship and Influence, and Algorithmic Learning by the Chinese Communist Party Act (ANTI-SOCIAL CCP Act), which would prohibit Chinese- and Russian-owned social networks from doing business in the United States.[337][338] That month, Senator Josh Hawley also introduced a separate measure, the No TikTok on Government Devices Act, to ban federal employees from using TikTok on all government devices.[339] On December 15, Hawley's measure was unanimously passed by the U.S. Senate.[340] On December 27, the Chief Administrative Officer of the United States House of Representatives banned TikTok from all devices managed by the House of Representatives.[341]

As of February 2023,[342][343] at least 32 (of 50) states have announced or enacted bans on state government agencies, employees, and contractors using TikTok on government-issued devices. State bans only affect government employees and do not prohibit civilians from having or using the app on their personal devices.

In March 2023, Politico reported that TikTok hired SKDK to lobby amid a possible federal ban.[344] This preceded TikTok's CEO appearance before Congress to address the concerns surrounding the app. He stated that TikTok's data collection practices did not differ from those of other US social media platforms.[345] A researcher at the Citizen Lab believes that governments around the world should better protect user information in general from being exploited by Big Tech, not focus exclusively on one app.[257]

Montana became the first state to pass legislation banning TikTok on all personal devices from operating within state lines and barring app stores from offering TikTok for downloads.[346][347][348] State governor Greg Gianforte signed the bill in May 2023 with the law going into effect in January 2024.[346][347][349] TikTok is paying the attorney fees for a lawsuit from Montana content creators who had expressed concerns about the legislation. The company is filing a separate case on its own behalf to overturn the ban.[350]

Commentary[edit]

Security officials have few details to offer about the move against TikTok.[13]

Attempts to ban TikTok by the United States have been regarded as hypocritical and politically motivated. The U.S. is headquarters to major global Internet companies, and its intelligence agencies such as the NSA can broadly interpret Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) to search user communications even without a warrant. Non-US persons are more easily targeted, numbering 232,432 in 2021, but US citizens' communications can also be caught up.[351]

The types of data collected by TikTok are also collected by other social media platforms and available for purchase through brokers, often without oversight, by both private and state entities.[351] A researcher at Georgia Tech’s Internet Governance Project raised the question of whether protectionism of U.S. corporations, rather than privacy concerns, is the primary motivation of the US government. An analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies writes that it would make more sense to focus on the protection of data directly rather than on any particular platform.[352]

Project Texas[edit]

Following Trump administration's attempt to ban the platform, TikTok has been working to silo privileged user data within the United States under oversight from the US government or a third party such as Oracle.[257] Named Project Texas, the initiative focuses on unauthorized access, state influence, and software security. A new subsidiary, TikTok U.S. Data Security Inc. (USDS), was created to manage user data, software code, back-end systems, and content moderation. It would report to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), not ByteDance or TikTok, even for hiring practices. Oracle would review and spot check the data flows through USDS. It would also digitally sign software code, approve updates, and oversee content moderation and recommendation. Physical locations would be established so that Oracle and the US government could conduct their own reviews.[353] The company has been engaged in confidential negotiations over the project with CFIUS since 2021 and submitted its proposal but received little response from the panel afterward.[354]

In March 2023, a former employee of the company said Project Texas did not go far enough and that a complete "re-engineering" would be needed. TikTok responded by saying that Project Texas already is a re-engineering of the app and that the former employee left in 2022 before the project specifications were finalized.[355]

Oceania[edit]

By 7 March 2023, 68 Australian federal agencies had banned TikTok on work-related mobile devices. Liberal Party Senator James Paterson called for a federal ban on all government-related devices.[356] In April, West Australian Premier Mark McGowan banned TikTok from government phones.[357]

On 17 March 2023, the New Zealand Parliamentary Service banned TikTok on devices connected to Parliament, citing cybersecurity concerns.[358][359]

Other legal issues[edit]

Some countries have shown concerns regarding the content on TikTok, as their cultures view it as obscene, immoral, vulgar, and encouraging pornography. There have been temporary blocks and warnings issued by countries including Indonesia,[360] Bangladesh,[361] India,[362] and Pakistan[363][364] over the content concerns. In 2018, Douyin was reprimanded by Chinese media watchdogs for showing "unacceptable" content.[365]

On 27 July 2020, Egypt sentenced five women to two years in prison over TikTok videos. One of the women had encouraged other women to try and earn money on the platform, another woman was sent to prison for dancing. The court also imposed a fine of 300,000 Egyptian pounds (UK£14,600) on each defendant.[366]

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita filed lawsuits against TikTok, alleging that the platform exposed inappropriate content to minors. The complaint also alleges that TikTok "intentionally falsely reports the frequency of sexual content, nudity, and mature/suggestive themes" on their platform which made the app's "12-plus" age ratings on the Apple and Google app stores deceptive.[367][368]

Tencent lawsuits[edit]

Tencent's WeChat platform has been accused of blocking Douyin's videos.[369][370] In April 2018, Douyin sued Tencent and accused it of spreading false and damaging information on its WeChat platform, demanding CN¥1 million in compensation and an apology. In June 2018, Tencent filed a lawsuit against Toutiao and Douyin in a Beijing court, alleging they had repeatedly defamed Tencent with negative news and damaged its reputation, seeking a nominal sum of CN¥1 in compensation and a public apology.[371] In response, Toutiao filed a complaint the following day against Tencent for allegedly unfair competition and asking for CN¥90 million in economic losses.[372]

Data transfer class action lawsuit[edit]

In November 2019, a class action lawsuit was filed in California that alleged that TikTok transferred personally identifiable information of U.S. persons to servers located in China owned by Tencent and Alibaba.[373][374][375] The lawsuit also accused ByteDance, TikTok's parent company, of taking user content without their permission. The plaintiff of the lawsuit, college student Misty Hong, downloaded the app but said she never created an account. She realized a few months later that TikTok has created an account for her using her information (such as biometrics) and made a summary of her information. The lawsuit also alleged that information was sent to Chinese tech giant Baidu.[376] In July 2020, twenty lawsuits against TikTok were merged into a single class action lawsuit in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois.[377] In February 2021, TikTok agreed to pay $92 million to settle the class action lawsuit.[378]

Voice actor lawsuit[edit]

In May 2021, Canadian voice actor Bev Standing filed a lawsuit against TikTok over the use of her voice in the text-to-speech feature without her permission. The lawsuit was filed in the Southern District of New York. TikTok declined to comment. Standing believes that TikTok used recordings she made for the Chinese government-run Institute of Acoustics.[379] The voice used in the feature was subsequently changed.[380]

Market Information Research Foundation lawsuit[edit]

In June 2021, the Netherlands-based Market Information Research Foundation (SOMI) filed a €1.4 billion lawsuit on behalf of Dutch parents against TikTok, alleging that the app gathers data on children without adequate permission.[381]

Blackout Challenge lawsuits[edit]

Multiple lawsuits have been filed against TikTok, accusing the platform of hosting content that led to the death of at least seven children.[382] The lawsuits claim that children died after attempting the "Blackout challenge", a TikTok trend that involves strangling or asphyxiating someone or themselves until they black out (passing out). TikTok stated that search queries for the challenge do not show any results, linking instead to protective resources, while the parents of two of the deceased argued that the content showed up on their children's TikTok feeds, without them searching for it.[383]

Cooperation with law enforcement[edit]

In June 2023 The New Zealand Herald reported that TikTok, working in cooperation with both New Zealand and Australian police, deleted 340 accounts and 2,000 videos associated with criminal gangs including the Mongrel Mob, Black Power, Killer Beez, the Comancheros, Mongols, and Rebels. TikTok had earlier drawn criticism for hosting content by organised crime groups promoting the gang lifestyle and fights. A TikTok spokesperon reiterated the platform's efforts to countering "violent" and "hateful" organisations' content and cooperating with police. New Zealand Police Commissioner Andrew Coster praised the platform for taking a "socially-responsible stance" against gangs.[384]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Strictly legal explainers are still available on topics such as same-sex marriage.

References[edit]

- ↑ "TikTok – Make Your Day". iTunes. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ↑ "抖音". App Store. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lin, Pellaeon (22 March 2021). "TikTok vs Douyin: A Security and Privacy Analysis". Citizen Lab. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ Isaac, Mike (8 October 2020). "U.S. Appeals Injunction Against TikTok Ban". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 December 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ Kastrenakes, Jacob (1 July 2021). "TikTok is rolling out longer videos to everyone". The Verge. Vox Media. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ↑ Geyser, Werner (11 January 2019). "50 TikTok Stats That Will Blow Your Mind [Updated 2020]". Influencer Marketing Hub. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ Sachwani, Anusha (15 February 2019). "TikTok Downloads: Countries with Most User Base Revealed!". Brandsynario. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). "TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads". The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ "2020年春季报告:抖音用户规模达5.18亿人次,女性用户占比57%" [2020 Spring Report: Douyin has 518 million users, 57% of whom are female] (in 中文). 22 April 2020. Archived from the original on 22 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Shahzad, Asif; Ahmad, Jibran (11 March 2021). "Pakistan to block social media app TikTok over 'indecency' complaint". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ "The Fastest Growing Brands of 2020". Morning Consult. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ↑ "TikTok surpasses Google as most popular website of the year, new data suggests". NBC News. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Goujard, Clothilde (22 March 2023). "What the hell is wrong with TikTok?". Politico.

- ↑ Campo, Richard (24 July 2023). "Is TikTok a national security threat?". Chicago Policy Review.

- ↑ Shead, Sam (8 October 2020). "What a TikTok exec told the British government about the app that we didn't already know". CNBC.

- ↑ "Beijing takes stake, board seat in ByteDance's key China entity - The Information". Reuters. 16 August 2021. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ "China state firms invest in TikTok sibling, Weibo chat app". Associated Press. 18 August 2021. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ↑ Whalen, Jeanne (17 August 2021). "Chinese government acquires stake in domestic unit of TikTok owner ByteDance in another sign of tech crackdown". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ↑ Feng, Coco (17 August 2021). "Chinese government takes minority stake, board seat in TikTok owner ByteDance's main domestic subsidiary". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "China's communist authorities are tightening their grip on the private sector". The Economist. 18 November 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ↑ "Fretting about data security, China's government expands its use of 'golden shares'". Reuters. 15 December 2021. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ↑ "China moves to take 'golden shares' in Alibaba and Tencent units". Financial Times. 13 January 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- ↑ "The App That Launched a Thousand Memes | Sixth Tone". Sixth Tone. 20 February 2018. Archived from the original on 23 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ "Is Douyin the Right Social Video Platform for Luxury Brands? | Jing Daily". Jing Daily. 11 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ↑ Graziani, Thomas (30 July 2018). "How Douyin became China's top short-video App in 500 days". WalktheChat. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ "8 Lessons from the rise of Douyin (Tik Tok) · TechNode". TechNode. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 11 March 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ "TikTok is owned by a Chinese company. So why doesn't it exist there?". CNN. 24 March 2023. Retrieved 13 July 2023.

- ↑ "Forget The Trade War. TikTok Is China's Most Important Export Right Now". BuzzFeed News. 16 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 24 May 2019.

- ↑ Niewenhuis, Lucas (25 September 2019). "The difference between TikTok and Douyin". SupChina. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2020.

- ↑ "TikTok's Rise to Global Markets". hbsp.harvard.edu. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ↑ "Tik Tok, a Global Music Video Platform and Social Network, Launches in Indonesia". Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ↑ "Tik Tok, Global Short Video Community launched in Thailand with the latest AI feature, GAGA Dance Machine The very first short video app with a new function based on AI technology". thailand.shafaqna.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ↑ Carman, Ashley (29 April 2020). "TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads". The Verge. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ↑ Doyle, Brandon (6 October 2020). "TikTok Statistics - Everything You Need to Know [Sept 2020 Update]". Wallaroo Media. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ↑ Yurieff, Kaya (21 November 2018). "TikTok is the latest social network sensation". Cnn.com. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019.

- ↑ Alexander, Julia (15 November 2018). "TikTok surges past 6M downloads in the US as celebrities join the app". The Verge. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ Spangler, Todd (20 November 2018). "TikTok App Nears 80 Million U.S. Downloads After Phasing Out Musical.ly, Lands Jimmy Fallon as Fan". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ↑ "A-Rod & J.Lo, Reese Witherspoon and the Rest of the A-List Celebs You Should Be Following on TikTok". People. Archived from the original on 28 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ Yuan, Lin; Xia, Hao; Ye, Qiang (16 August 2022). "The effect of advertising strategies on a short video platform: evidence from TikTok". Industrial Management & Data Systems. 122 (8): 1956–1974. doi:10.1108/IMDS-12-2021-0754. ISSN 0263-5577. S2CID 251508287.