Treaty of Indus

Thank you for being part of the Bharatpedia family! 0% transparency: ₹0 raised out of ₹100,000 (0 supporter) |

The ancient Greecian Historians Justin, Appian, and Strabo preserve the three main terms of the Treaty of the Indus:[1]

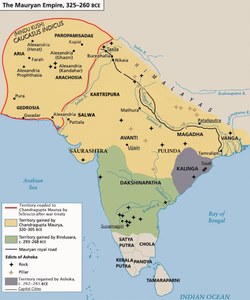

- (i) Seleucus transferred to Chandragupta's kingdom the easternmost satrapies of his empire, certainly Gandhara, Paropamisadae, and the eastern parts of Gedrosia, Arachosia and Aria as far as Herat.

- (ii) Chandragupta Maurya gave Seleucus 500 Indian war elephants.

- (iii) Epigamia: The two kings were joined by some kind of marriage alliance (ἐπιγαμία οι κῆδος); most likely Chandragupta wed a female relative of Seleucus.

Conflict and alliance with Seleucus (305 BCE)[edit]

Seleucus I Nicator, the Macedonian satrap of the Asian portion of Alexander's former empire, conquered and put under his own authority eastern territories as far as Bactria and the Indus (Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55), until in 305 BCE he entered into a confrontation with Emperor Chandragupta:

Always lying in wait for the neighbouring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he [Seleucus] acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.

It is clear that Seleucus fared poorly against the Indian Emperor as he failed to conquer any territory, and in fact was forced to surrender much that was already his. Regardless, Seleucus and Chandragupta ultimately reached a settlement and through a treaty sealed in 305 BCE, Seleucus, according to Strabo, ceded a number of territories to Chandragupta, including eastern Afghanistan and Balochistan.[citation needed]

Marriage alliance[edit]

Chandragupta and Seleucus concluded a peace treaty and a marriage alliance in 303 BCE. Chandragupta received vast territories and in a return gave Seleucus 500 war elephants,[7][8][9][10][11] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.[12] In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar). Later, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[13][better source needed]

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern-day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[14][15] Archaeologically, concrete indications of Mauryan rule, such as the inscriptions of the Edicts of Ashoka, are known as far as Kandahar in southern Afghanistan.

He (Seleucus) crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship.

After having made a treaty with him (Sandrakotos) and put in order the Orient situation, Seleucos went to war against Antigonus.

— Junianus Justinus, Historiarum Philippicarum, libri XLIV, XV.4.15

The treaty on "Epigamia" implies lawful marriage between Greeks and Indians was recognized at the State level, although it is unclear whether it occurred among dynastic rulers or common people, or both.[citation needed]

Indian source Bhavishya Purana also mentioned about Chandrgupta marriage:

śakyāsihāduddhasiṁhaḥ piturarddha kṛtaṁ padam॥ candraguptastasya sutaḥ paurasādhi pateḥ sutām। sulūvasya tathodvahya yāvanī baudhatatparaḥ।। ṣaṣṭhivarṣa kṛtaṁ rājyaṁ bindusārastatobhavat। pitṛstulyaṁ kṛtaṁ rājyamaśokastanayo'bhavat ।।

(Bhavishya Purana - Pratisarga Parva 1: Chapter 6, Verse 43,44)[16]

Translation: The descendants of Shakyasingh became Lord Buddha, who ruled for half of his father's time. Chandragupta, a descendant of Buddha, married the Buddhist daughter of the Greek ruler Seleucus, and he ruled for sixty years. After him, Bindusara, ruled, and eventually, Ashoka emerged as a significant ruler, continuing the lineage of Bindusara.

Exchange of presents[edit]

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:[17]

And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amorous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love.

His son Bindusara 'Amitraghata' (Slayer of Enemies) also is recorded in Classical sources as having exchanged presents with Antiochus I:[17]

But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece.

References[edit]

- ↑ Kosmin, Paul J. (2014-06-23). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- ↑ "Appian, The Syrian Wars 11". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Bachhofer, Ludwig (1929). Early Indian Sculpture Vol. I. Paris: The Pegasus Press. pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Page 122: About the Masarh lion: "This particular example of a foreign model gets added support from the male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath since they also prove beyond doubt that a section of the elite in the Gangetic Basin was of foreign origin. However, as noted earlier, this is an example of the late Mauryan period since this is not the type adopted in any Ashoka pillar. We are, therefore, visualizing a historical situation in India in which the West Asian influence on Indian art was felt more in the late Mauryan than in the early Mauryan period. The term West Asia in this context stands for Iran and Afghanistan, where the Sakas and Pahlavas had their base-camps for eastward movement. The prelude to future inroads of the Indo-Bactrians in India had after all started in the second century B.C."... in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. pp. 88, 122. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3..

- ↑ According to Gupta this is a non-Indian face of a foreigner with a conical hat: "If there are a few faces which are nonIndian, such as one head from Sarnath with conical cap ( Bachhofer, Vol . I, Pl . 13 ), they are due to the presence of the foreigners their costumes, tastes and liking for portrait art and not their art styles." in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3.

- ↑ Annual Report 1907-08. 1911. p. 55.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Ancient India, (Kachroo, p.196)

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Hunter, p.167)

- ↑ The evolution of man and society (Darlington, p.223)

- ↑ W. W. Tarn (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 60, p. 84–94.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, H. T. Riley)". Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Walter Eugene Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology", Classical Philology 14 (4), pp. 297–313.

- ↑ Khem Raj Shri Krishna Lal, Shri Venkateshwar Steam Press. Bhavishya Maha Puran, 1959 Khem Raj Shri Krishna Lal, Shri Venkateshwar Steam Press, Mumbai.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kosmin 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ "Problem while searching in The Literature Collection". Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Literature Collection: The deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the learned of Athenæus (volume III): Book XIV". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

This article does not have any categories. Please add a category so that it will be placed in a dynamic list with other articles like it. (November 2023) |