Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Владимир Путин | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Putin in 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Assumed office 7 May 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Dmitry Medvedev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 7 May 2000 – 7 May 2008 Acting: 31 December 1999 – 7 May 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Boris Yeltsin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister of Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 May 2008 – 7 May 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Dmitry Medvedev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Viktor Zubkov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 9 August 1999 – 7 May 2000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Boris Yeltsin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First Deputy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Sergei Stepashin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Kasyanov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Secretary of the Security Council | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 9 March 1999 – 9 August 1999 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Boris Yeltsin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolay Bordyuzha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Sergei Ivanov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Director of the Federal Security Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 25 July 1998 – 29 March 1999 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President | Boris Yeltsin | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Nikolay Kovalyov | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Patrushev | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin 7 October 1952 Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | Independent (1991–1995; 2001–2008; 2012–present) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | People's Front (2011–present) United Russia[1] (2008–2012) Unity (1999–2001) Our Home – Russia (1995–1999) CPSU (1975–1991) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouse(s) | [lower-alpha 1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | At least 2, Maria and Katerina[lower-alpha 2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parent(s) | Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin Maria Ivanovna Putina | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Residence | Novo-Ogaryovo, Moscow | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Saint Petersburg State University (LLB) Saint Petersburg Mining Institute (PhD) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Awards | Order of Honour | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | eng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Military service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Soviet Union Russia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Branch/service | KGB; FSB; Russian Armed Forces | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years of service |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rank | Colonel Supreme Commander-in-Chief | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Battles/wars | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Incumbent Policies Elections Premiership

Media gallery |

||

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin[lower-alpha 3] (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who is the president of Russia, a position he has filled since 2012, and previously from 1999 until 2008.[7][lower-alpha 4] He was also the prime minister from 1999 to 2000, and again from 2008 to 2012. Putin is the second-longest current serving European president after Alexander Lukashenko.

Putin was born in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) and studied law at Leningrad State University, graduating in 1975. He worked as a KGB foreign intelligence officer for 16 years, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel, before resigning in 1991 to begin a political career in Saint Petersburg. He moved to Moscow in 1996 to join the administration of president Boris Yeltsin. He briefly served as director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and secretary of the Security Council, before being appointed as prime minister in August 1999. After the resignation of Yeltsin, Putin became acting president, and less than four months later was elected outright to his first term as president and was reelected in 2004. As he was then constitutionally limited to two consecutive terms as president, Putin served as prime minister again from 2008 to 2012 under Dmitry Medvedev, and returned to the presidency in 2012 in an election marred by allegations of fraud and protests; he was reelected again in 2018. In April 2021, following a referendum, he signed into law constitutional amendments including one that would allow him to run for reelection twice more, potentially extending his presidency to 2036.[8][9]

During Putin's first tenure as president, the Russian economy grew for eight consecutive years, with GDP measured by purchasing power increasing by 72%; Russian self-assessed life satisfaction rose significantly.[10] The growth was a result of a fivefold increase in the price of oil and gas, which constitute the majority of Russian exports, recovery from the post-communist depression and financial crises, a rise in foreign investment,[11] and prudent economic and fiscal policies.[12][13] Putin also led Russia to victory in the Second Chechen War. Serving as prime minister under Medvedev, he oversaw large-scale military reform and police reform, as well as Russia's victory in the Russo-Georgian War. During his third term as president, falling oil prices coupled with international sanctions imposed at the beginning of 2014 after Russia launched a military intervention in Ukraine and annexed Crimea led to GDP shrinking by 3.7% in 2015, though the Russian economy rebounded in 2016 with 0.3% GDP growth.[14] During his fourth term as president, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Russia, and Putin ordered a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, leading to further sanctions being imposed against Russia and him personally. Other developments under Putin have included the construction of oil and gas pipelines, the restoration of the satellite navigation system GLONASS, and the building of infrastructure for international events such as the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi and the 2018 FIFA World Cup.

Under Putin's leadership, Russia has shifted to authoritarianism. Experts do not consider Russia a democracy, citing the jailing and repression of political opponents, the intimidation and suppression of the free press and the lack of free and fair elections.[15][16][17] Russia has scored poorly on Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index, and Freedom House's Freedom in the World index.

Early life[edit]

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was born on 7 October 1952 in Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia),[18][19] the youngest of three children of Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (1911–1999) and Maria Ivanovna Putina (née Shelomova; 1911–1998). Spiridon Putin, Vladimir Putin's grandfather, was a personal cook to Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.[20][21] Putin's birth was preceded by the deaths of two brothers, Viktor and Albert, born in the mid-1930s. Albert died in infancy and Viktor died of diphtheria during the Siege of Leningrad by Nazi Germany's forces in World War II.[22]

Putin's mother was a factory worker and his father was a conscript in the Soviet Navy, serving in the submarine fleet in the early 1930s. Early in World War II, his father served in the destruction battalion of the NKVD.[23][24][25] Later, he was transferred to the regular army and was severely wounded in 1942.[26] Putin's maternal grandmother was killed by the German occupiers of Tver region in 1941, and his maternal uncles disappeared on the Eastern Front during World War II.[27]

On 1 September 1960, Putin started at School No. 193 at Baskov Lane, near his home. He was one of a few in the class of approximately 45 pupils who were not yet members of the Young Pioneer organization. At age 12, he began to practise sambo and judo.[28] In his free time he enjoyed reading on Marx, Engels and Lenin.[29] Putin studied German at Saint Petersburg High School 281 and speaks German as a second language.[30]

Putin studied law at the Leningrad State University named after Andrei Zhdanov (now Saint Petersburg State University) in 1970 and graduated in 1975.[31] His thesis was on "The Most Favored Nation Trading Principle in International Law".[32] While there, he was required to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and remained a member until it ceased to exist (it was outlawed in August 1991).[33] Putin met Anatoly Sobchak, an assistant professor who taught business law,[lower-alpha 5] and later became the co-author of the Russian constitution and of the corruption schemes persecuted in France. Putin would be influential in Sobchak's career in Saint Petersburg. Sobchak would be influential in Putin's career in Moscow.[34]

KGB career[edit]

In 1975, Putin joined the KGB and trained at the 401st KGB school in Okhta, Leningrad.[18][35] After training, he worked in the Second Chief Directorate (counter-intelligence), before he was transferred to the First Chief Directorate, where he monitored foreigners and consular officials in Leningrad.[18][36][37] In September 1984, Putin was sent to Moscow for further training at the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute.[38][39][40] From 1985 to 1990, he served in Dresden, East Germany,[41] using a cover identity as a translator.[42] This period in his career is mostly unclear.

Masha Gessen, a Russian-American who has authored a biography about Putin, claims "Putin and his colleagues were reduced mainly to collecting press clippings, thus contributing to the mountains of useless information produced by the KGB".[42] Putin's work was also downplayed by former Stasi spy chief Markus Wolf and Putin's former KGB colleague Vladimir Usoltsev. According to journalist Catherine Belton, this downplaying was actually cover for Putin's involvement in KGB coordination and support for the terrorist Red Army Faction, whose members were frequently hiding in East Germany with support of the Stasi, and Dresden was preferred as a "marginal" town with low presence of Western intelligence services.[43]

According to an anonymous source, a former RAF member, at one of these meetings in Dresden the militants presented Putin with a list of weapons that were later delivered to the RAF in West Germany. Klaus Zuchold, who claimed to be recruited by Putin, said the latter also handled a neo-nazi Rainer Sonntag, and attempted to recruit an author of a study on poisons.[43] Putin also reportedly met Germans to be recruited for wireless communications affairs together with an interpreter. He was involved in wireless communications technologies in South-East Asia due to trips of German engineers, recruited by him, there and to the West.[37]

According to Putin's official biography, during the fall of the Berlin Wall that began on 9 November 1989, he saved the files of the Soviet Cultural Center (House of Friendship) and of the KGB villa in Dresden for the official authorities of the would-be united Germany to prevent demonstrators, including KGB and Stasi agents, from obtaining and destroying them. He then supposedly burnt only the KGB files, in a few hours, but saved the archives of the Soviet Cultural Center for the German authorities. Nothing is told about the selection criteria during this burning; for example, concerning Stasi files or about files of other agencies of the German Democratic Republic or of the USSR. He explained that many documents were left to Germany only because the furnace burst. But many documents of the KGB villa were sent to Moscow.[44]

After the collapse of the Communist East German government, Putin was to resign from active KGB service because of suspicions aroused regarding his loyalty during demonstrations in Dresden and earlier, though the KGB and the Soviet Red Army still operated in eastern Germany, and he returned to Leningrad in early 1990 as a member of the "active reserves", where he worked for about three months with the International Affairs section of Leningrad State University, reporting to Vice-Rector Yuriy Molchanov,[37] while working on his doctoral dissertation.

There, he looked for new KGB recruits, watched the student body, and renewed his friendship with his former professor, Anatoly Sobchak, soon to be the Mayor of Leningrad.[45] Putin claims that he resigned with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel on 20 August 1991,[45] on the second day of the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt against the Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev.[46] Putin said: "As soon as the coup began, I immediately decided which side I was on", although he also noted that the choice was hard because he had spent the best part of his life with "the organs".[47]

In 1999, Putin described communism as "a blind alley, far away from the mainstream of civilization".[48]

Political career[edit]

Domestic policies[edit]

Foreign policy[edit]

Public image[edit]

Polls and rankings[edit]

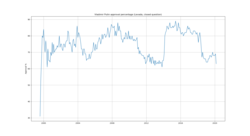

According to a June 2007 public opinion survey, Putin's approval rating was 81%, the second highest of any leader in the world that year.[49] In January 2013, at the time of the 2011–2013 Russian protests, Putin's approval rating fell to 62%, the lowest figure since 2000 and a ten-point drop over two years.[50]

By May 2014, Putin's approval rating hit its highest since 2008, and was 83%. After EU and U.S. sanctions against Russian officials as a result of the crisis in Ukraine, Putin's approval rating reached 87%, according to a survey published on 6 August 2014.[51] In February 2015, based on new domestic polling, Putin was ranked the world's most popular politician.[52] In June 2015, Putin's approval rating climbed to 89%, an all-time high.[53][54][55] In 2016, the approval rating was 81%.[56]

Observers saw Putin's high approval ratings in 2010's as a consequence of significant improvements in living standards, and Russia's reassertion of itself on the world scene during his presidency.[57][58]

Despite high approval for Putin, confidence in the Russian economy was low, dropping to levels in 2016 that rivaled the recent lows in 2009 at the height of the global economic crisis. Just 14% of Russians in 2016 said their national economy was getting better, and 18% said this about their local economies.[59] Putin's performance at reining in corruption is also unpopular among Russians. Newsweek reported in June 2017 that "An opinion poll by the Moscow-based Levada Center indicated that 67 percent held Putin personally responsible for high-level corruption".[60]

In July 2018, Putin's approval rating fell to 63% and just 49% would vote for Putin if presidential elections were held.[62] Levada poll results published in September 2018 showed Putin's personal trustworthiness levels at 39% (decline from 59% in November 2017)[63] with the main contributing factor being the presidential support of the unpopular pension reform and economic stagnation.[64][65] In October 2018, two-thirds of Russians surveyed in Levada poll agreed that "Putin bears full responsibility for the problems of the country" which has been attributed[66] to decline of a popular belief in "good tsar and bad boyars", a traditional attitude towards justifying failures of top of ruling hierarchy in Russia.[67]

In January 2019, the percentage of Russians trusting the president hit a then-historic minimum – 33.4%.[68] It declined further to 31.7% in May 2019[69] which led to a dispute between the VCIOM and President's administration office, who accused it of incorrectly using an open question, after which VCIOM repeated the poll with a closed question getting 72.3%.[70] Nonetheless, in April 2019 Gallup poll showed a record number of Russians (20%) willing to permanently emigrate from Russia.[71] The decline is even larger in the 17–25 age group, "who find themselves largely disconnected from the country's aging leadership, nostalgic Soviet rhetoric and nepotistic agenda", according to a report prepared by Vladimir Milov. The percentage of people willing to emigrate permanently in this age group is 41% and 60% has favorable views on the United States (three times more than in the 55+ age group).[72] Decline in support for president and the government is also visible in other polls, such as rapidly growing readiness to protest against poor living conditions.[70]

In May 2020, amid the COVID-19 crisis, Putin's approval rating was 67.9%, measured by VCIOM when respondents were presented a list of names (closed question),[73] and 27% when respondents were expected to name politicians they trust (open question).[74] In a closed-question survey conducted by Levada, the approval rating was 59%[75] which has been attributed to continued post-Crimea economic stagnation but also an apathetic response to the pandemic crisis in Russia.[76] In another May 2021 Levada poll, 33% indicated Putin in response to "who would you vote for this weekend?" among Moscow respondents and 40% outside of Moscow.[77] The Levada Center survey released in October 2021 found 53% of respondents saying they trusted Putin.[78]

Polls conducted in November 2021 on the wake of failure of Russian COVID-19 vaccination campaign indicated that distrust of Putin personally are one of the major contributing factor for vaccine hesitancy among citizens, with regional polls indicating numbers as low as 20–30% in Volga Federal District.[79]

Assessments[edit]

Critics state that Putin has moved Russia in an autocratic direction, weakening the system of representative government advocated by Boris Yeltsin.[81] Putin has been described as a "dictator" by political opponent Garry Kasparov,[82] as a "bully" and "arrogant" by former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton,[83][84][85] and as "self-centered" by the Dalai Lama.[86] Former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote in 2014 that the West has demonized Putin.[87] Egon Krenz, former leader of East Germany, said the Cold War never ended and that, "After weak presidents like Gorbachev and Yeltsin, it is a great fortune for Russia that it has [President Vladimir] Putin."[88]

Many Russians credit Putin for reviving Russia's fortunes.[89] Former Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev, while acknowledging the flawed democratic procedures and restrictions on media freedom during the Putin presidency, said that Putin had pulled Russia out of chaos at the end of the Yeltsin years, and that Russians "must remember that Putin saved Russia from the beginning of a collapse."[89][90] In 2015, opposition politician Boris Nemtsov said that Putin was turning Russia into a "raw materials colony" of China.[91] Chechen Republic head and Putin supporter, Ramzan Kadyrov, states that Putin saved both the Chechen people and Russia.[92]

Russia has suffered democratic backsliding during Putin's tenure. Freedom House has listed Russia as being "not free" since 2005.[93] Experts do not generally consider Russia to be a democracy, citing purges and jailing of political opponents, curtailed press freedom, and the lack of free and fair elections.[94][95][16][17][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104] In 2004, Freedom House warned that Russia's "retreat from freedom marks a low point not registered since 1989, when the country was part of the Soviet Union."[105] The Economist Intelligence Unit has rated Russia as "authoritarian" since 2011,[106] whereas it had previously been considered a "hybrid regime" (with "some form of democratic government" in place) as late as 2007.[107] According to political scientist Larry Diamond, writing in 2015, "no serious scholar would consider Russia today a democracy".[108]

Personal image[edit]

Putin cultivates an outdoor, sporty, tough guy public image, demonstrating his physical prowess and taking part in unusual or dangerous acts, such as extreme sports and interaction with wild animals,[109] part of a public relations approach that, according to Wired, "deliberately cultivates the macho, take-charge superhero image".[110] For example, in 2007, the tabloid Komsomolskaya Pravda published a huge photograph of a shirtless Putin vacationing in the Siberian mountains under the headline: "Be Like Putin."[111] Numerous Kremlinologists have accused Putin of seeking to create a cult of personality around himself, an accusation that the Kremlin has denied.[112] Some of Putin's activities have been criticised for being staged;[113][114] outside of Russia, his macho image has been the subject of parody.[115][116][117] Putin is believed to be self-conscious about his height, which has been estimated by Kremlin insiders at between 155 and 165 centimetres (5 feet 1 inch and 5 feet 5 inches) tall but is usually given at 170 centimetres (5 feet 7 inches).[118][119]

There are many songs about Putin,[120] and Putin's name and image are widely used in advertisement and product branding.[110] Among the Putin-branded products are Putinka vodka, the PuTin brand of canned food, the Gorbusha Putina caviar, and a collection of T-shirts with his image.[121] In 2015, his advisor Mikhail Lesin was found dead after "days of excessive consumption of alcohol", though this was later ruled an accident.[122]

Publication recognition in the United States[edit]

In 2007, he was the Time Person of the Year.[123][124] In 2015, he was No. 1 on the Time's Most Influential People List.[125][126] Forbes ranked him the World's Most Powerful Individual every year from 2013 to 2016.[127] He was ranked the second most powerful individual by Forbes in 2018.[128]

Putinisms[edit]

Putin has produced many aphorisms and catch-phrases known as putinisms.[129] Many of them were first made during his annual Q&A conferences, where Putin answered questions from journalists and other people in the studio, as well as from Russians throughout the country, who either phoned in or spoke from studios and outdoor sites across Russia. Putin is known for his often tough and sharp language, often alluding to Russian jokes and folk sayings.[129]

Putin sometimes uses Russian criminal jargon (known as "fenya" in Russian), albeit not always correctly.[130]

Electoral history[edit]

Personal life[edit]

Family[edit]

On 28 July 1983, Putin married Lyudmila Shkrebneva, and they lived together in East Germany from 1985 to 1990. They have two daughters, Mariya Putina, born 28 April 1985 in Leningrad, and Yekaterina Putina, born 31 August 1986 in Dresden, East Germany.[131]

An investigation by Proekt Media published in November 2020 alleged that Putin has another daughter, Elizaveta (known as Luiza Rozova[132]), born March 2003,[133] with Svetlana Krivonogikh.[4][134]

In April 2008, the Moskovsky Korrespondent reported that Putin had divorced Lyudmila and was engaged to marry Olympic gold medalist Alina Kabaeva, a former rhythmic gymnast and Russian politician.[2] The story was denied[2] and the newspaper was shut down shortly thereafter.[3] Putin and Lyudmila continued to make public appearances together as spouses, while the status of his relationship with Kabaeva became a topic of speculation.[135][136][137][138] In the subsequent years, there were frequent unsubstantiated reports that Putin and Kabaeva had multiple children together, although these reports were denied.[139]

On 6 June 2013, Putin and Lyudmila announced that their marriage was over, and, on 1 April 2014, the Kremlin confirmed that the divorce had been finalised.[140][141][142] In 2015, Kabaeva reportedly gave birth to a daughter; Putin is alleged to be the father.[139][136][5] In 2019, Kabaeva reportedly gave birth to twin sons by Putin.[6][143]

Putin has two grandsons, born in 2012 and 2017.[144][145]

His cousin, Igor Putin, was a director at Moscow-based Master Bank and was accused in a number of money laundering scandals.[146][147]

Personal wealth[edit]

Official figures released during the legislative election of 2007 put Putin's wealth at approximately 3.7 million rubles (US$150,000) in bank accounts, a private 77.4-square-meter (833 sq ft) apartment in Saint Petersburg, and miscellaneous other assets.[148][149] Putin's reported 2006 income totaled 2 million rubles (approximately $80,000). In 2012, Putin reported an income of 3.6 million rubles ($113,000).[150][151]

Putin has been photographed wearing a number of expensive wristwatches, collectively valued at $700,000, nearly six times his annual salary.[152][153] Putin has been known on occasion to give watches valued at thousands of dollars as gifts to peasants and factory workers.[154]

According to Russian opposition politicians and journalists, Putin secretly possesses a multi-billion-dollar fortune[155][156] via successive ownership of stakes in a number of Russian companies.[157][158] According to one editorial in The Washington Post, "Putin might not technically own these 43 aircraft, but, as the sole political power in Russia, he can act like they're his".[159] Russian RIA journalist argued that "[Western] intelligence agencies (...) could not find anything". These contradictory claims were analyzed by Polygraph.info[160] which looked at a number of reports by Western (Anders Åslund estimate of $100–160 billion) and Russian (Stanislav Belkovsky estimated of $40 billion) analysts, CIA (estimate of $40 billion in 2007) as well as counterarguments of Russian media. Polygraph concluded:

There is uncertainty on the precise sum of Putin's wealth, and the assessment by the Director of U.S. National Intelligence apparently is not yet complete. However, with the pile of evidence and documents in the Panama Papers and in the hands of independent investigators such as those cited by Dawisha, Polygraph.info finds that Danilov's claim that Western intelligence agencies have not been able to find evidence of Putin's wealth to be misleading

— Polygraph.info, "Are 'Putin's Billions' a Myth?"

In April 2016, 11 million documents belonging to Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca were leaked to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The name of Vladimir Putin does not appear in any of the records, and Putin denied his involvement with the company.[161] However, various media have reported on three of Putin's associates on the list.[162] According to the Panama Papers leak, close trusted associates of Putin own offshore companies worth US$2 billion in total.[163] The German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung regards the possibility of Putin's family profiting from this money as plausible.[164][165]

According to the paper, the US$2 billion had been "secretly shuffled through banks and shadow companies linked to Putin's associates", such as construction billionaires Arkady and Boris Rotenberg, and Bank Rossiya, previously identified by the U.S. State Department as being treated by Putin as his personal bank account, had been central in facilitating this. It concludes that "Putin has shown he is willing to take aggressive steps to maintain secrecy and protect [such] communal assets."[166][167] A significant proportion of the money trail leads to Putin's best friend Sergei Roldugin. Although a musician, and in his own words, not a businessman, it appears he has accumulated assets valued at $100m, and possibly more. It has been suggested he was picked for the role because of his low profile.[162] There have been speculations that Putin, in fact, owns the funds,[168] and Roldugin just acted as a proxy.[169]

Garry Kasparov said, "[Putin] controls enough money, probably more than any other individual in the history of human race".[170]

Residences[edit]

Official government residences[edit]

As president and prime-minister, Putin has lived in numerous official residences throughout the country.[171] These residences include: the Moscow Kremlin, Novo-Ogaryovo in Moscow Oblast, Gorki-9 [ru] near Moscow, Bocharov Ruchey in Sochi, Dolgiye Borody [ru] in Novgorod Oblast, and Riviera in Sochi.[172]

In August 2012, critics of Putin listed the ownership of 20 villas and palaces, nine of which were built during Putin's 12 years in power.[173]

Personal residences[edit]

Soon after Putin returned from his KGB service in Dresden, East Germany, he built a dacha in Solovyovka on the eastern shore of Lake Komsomolskoye on the Karelian Isthmus in Priozersky District of Leningrad Oblast, near St. Petersburg. After the dacha burned down in 1996, Putin built a new one identical to the original and was joined by a group of seven friends who built dachas nearby. In 1996, the group formally registered their fraternity as a co-operative society, calling it Ozero ("Lake") and turning it into a gated community.[174]

A massive Italianate-style mansion costing an alleged US$1 billion[175] and dubbed "Putin's Palace" is under construction near the Black Sea village of Praskoveevka. In 2012, Sergei Kolesnikov, a former business associate of Putin's, told the BBC's Newsnight programme that he had been ordered by Deputy Prime Minister Igor Sechin to oversee the building of the palace.[176] He also said that the mansion, built on government land and sporting 3 helipads, a private road paid for from state funds and guarded by officials wearing uniforms of the official Kremlin guard service, have been built for Putin's private use.[177] Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov dismissed Kolesnikov's allegations against Putin as untrue, saying that "Putin has never had any relationship to this palace."[178] On 19 January 2021, two days after Alexei Navalny was detained by Russian authorities upon his return to Russia, a video investigation by him and the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) was published accusing Putin of using fraudulently obtained funds to build the estate for himself in what he called "the world's biggest bribe." In the investigation, Navalny said that the estate is 39 times the size of Monaco and cost over 100 billion rubles ($1.35 billion) to construct. It also showed aerial footage of the estate via a drone and a detailed floorplan of the palace that Navalny said was given by a contractor, which he compared to photographs from inside the palace that were leaked onto the Internet in 2011. He also detailed an elaborate corruption scheme allegedly involving Putin's inner circle that allowed Putin to hide billions of dollars to build the estate.[179][180][181]

Pets[edit]

Putin has received five dogs from various nation leaders: Konni, Buffy, Yume, Verni and Pasha. Konni died in 2014. When Putin first became president, the family had two poodles, Tosya and Rodeo. They reportedly stayed with his ex-wife Lyudmila after their divorce.[182]

Religion[edit]

Putin is Russian Orthodox. His mother was a devoted Christian believer who attended the Russian Orthodox Church, while his father was an atheist.[183] Though his mother kept no icons at home, she attended church regularly, despite government persecution of her religion at that time. His mother secretly baptized him as a baby, and she regularly took him to services.[26]

According to Putin, his religious awakening began after a serious car crash involving his wife in 1993, and a life-threatening fire that burned down their dacha in August 1996.[183] Shortly before an official visit to Israel, Putin's mother gave him his baptismal cross, telling him to get it blessed. Putin states, "I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since."[26] When asked in 2007 whether he believes in God, he responded, "... There are things I believe, which should not in my position, at least, be shared with the public at large for everybody's consumption because that would look like self-advertising or a political striptease."[184] Putin's rumoured confessor is Russian Orthodox Bishop Tikhon Shevkunov.[185] However, the sincerity of his Christianity has been rejected by his former advisor Sergei Pugachev.[186]

Sports[edit]

Putin watches football and supports FC Zenit Saint Petersburg.[187] He also displays an interest in ice hockey and bandy.[188]

Putin has been practicing judo since he was 11 years old,[189] before switching to sambo at the age of fourteen.[190] He won competitions in both sports in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg). He was awarded eighth dan of the black belt in 2012, becoming the first Russian to achieve the status.[191] Putin also practises karate.[192] He co-authored a book entitled Judo with Vladimir Putin in Russian, and Judo: History, Theory, Practice in English (2004).[193] Benjamin Wittes, a black belt in taekwondo and aikido and editor of Lawfare, has disputed Putin's martial arts skills, stating that there is no video evidence of Putin displaying any real noteworthy judo skills.[194][195]

Honours[edit]

Civilian awards presented by different countries[edit]

| Date | Country | Decoration | Presenter | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 March 2001 | Vietnam | Order of Ho Chi Minh[196] | Vietnam's second highest distinction | ||

| 2004 | Kazakhstan | Order of the Golden Eagle[197] | Kazakhstan's highest distinction | ||

| 22 September 2006 | France | Légion d'honneur[198] | President Jacques Chirac | Grand-Croix (Grand Cross) rank is the highest French decoration | |

| 2007 | Tajikistan | Order of Ismoili Somoni[199] | Tajikistan's highest distinction | ||

| 12 February 2007 | Saudi Arabia | Order of Abdulaziz al Saud[200] | King Abdullah | Saudi Arabia's highest civilian award | |

| 10 September 2007 | UAE | Order of Zayed[201] | Sheikh Khalifa | UAE's highest civil decoration | |

| 2 April 2010 | Venezuela | Order of the Liberator[202] | President Hugo Chávez | Venezuela's highest distinction | |

| 4 October 2013 | Monaco | Order of Saint-Charles[203] | Prince Albert | Monaco's highest decoration | |

| 11 July 2014 | Cuba | Order of José Martí[204] | President Raúl Castro | Cuba's highest decoration | |

| 16 October 2014 | Serbia | Order of the Republic of Serbia[205] | President Tomislav Nikolić | Grand Collar, Serbia's highest award | |

| 3 October 2017 | Turkmenistan | Order "For contribution to the development of cooperation" | President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow | ||

| 22 November 2017 | Kyrgyzstan | Order of Manas | President Almazbek Atambayev | ||

| 8 June 2018 | China | Order of Friendship[206] | President Xi Jinping | People's Republic of China's highest order of honour | |

| 28 May 2019 | Kazakhstan | Order of Nazarbayev[207] | Elbasy Nursultan Nazarbayev | ||

Honorary doctorates[edit]

| Date | University/ Institute |

|---|---|

| 2001 | Baku Slavic University[208] |

| 2001 | Yerevan State University[209] |

| 2001 | Athens University[210] |

| 2011 | University of Belgrade[211] |

Other awards[edit]

| Year | Award | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | Order of Sheikh ul-Islam | A Muslim order,[212] awarded for his role in interfaith dialogue between Muslims and Christians in the region.[213] |

| 24 March 2011 | Order of Saint Sava[214] | Serbian Orthodox Church's highest distinction. |

| 15 November 2011 | Confucius Peace Prize | The China International Peace Research Centre awarded the Confucius Peace Prize to Putin, citing as reason Putin's opposition to NATO's Libya bombing in 2011 while also paying tribute to his decision to go to war in Chechnya in 1999.[215] According to the committee, Putin's "Iron hand and toughness revealed in this war impressed the Russians a lot, and he was regarded to be capable of bringing safety and stability to Russia".[216] |

| 2015 | Angel of Peace Medal | Pope Francis presented Putin with the Angel of Peace Medal,[217] which is a customary gift to presidents visiting the Vatican.[218] |

Recognition[edit]

| Year | Award/Recognition | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Time: Person of the Year | "His final year as Russia's president has been his most successful yet. At home, he secured his political future. Abroad, he expanded his outsize—if not always benign—influence on global affairs."[219] |

| December 2007 | Expert: Person of the Year | A Russian business-oriented weekly magazine named Putin as its Person of the Year.[220] |

| 5 October 2008 | Vladimir Putin Avenue | The central street of Grozny, the capital of Russia's Republic of Chechnya, was renamed from the Victory Avenue to the Vladimir Putin Avenue, as ordered by the Chechen President Ramzan Kadyrov.[221] |

| February 2011 | Vladimir Putin Peak | The parliament of Kyrgyzstan named a peak in Tian Shan mountains Vladimir Putin Peak.[222] |

Notes[edit]

- ↑ The Putins officially announced their separation in 2013 and the Kremlin confirmed the divorce had been finalized in 2014; however, it has been alleged that Putin and Lyudmila divorced in 2008.[2][3]

- ↑ Putin has two daughters with his ex-wife Lyudmila. He is also alleged to have a third daughter with Svetlana Krivonogikh,[4] and a fourth daughter and twin sons with Alina Kabaeva,[5][6] although these reports have not been officially confirmed.

- ↑ /ˈpuːtɪn/; Russian: Владимир Владимирович Путин, [vlɐˈdʲimʲɪr vlɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪtɕ ˈputʲɪn] (

listen)

listen)

- ↑ Putin took office as Prime Minister in August 1999 and became Acting President while remaining Prime Minister on 31 December 1999; he was later officially elected as President on 7 May 2000.

- ↑ Russian: хозяйственное право, romanized: khozyaystvennoye pravo.

References[edit]

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin quits as head of Russia's ruling party". 24 April 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022 – via The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Putin Romance Rumors Keep Public Riveted". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 April 2008. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Herszenhorn, David M. (5 May 2012). Written at Moscow. "In the Spotlight of Power, Putin Keeps His Private Life Veiled in Shadows". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Zakharov, Andrey; Badanin, Roman; Rubin, Mikhail (25 November 2020). "An investigation into how a close acquaintance of Vladimir Putin attained a piece of Russia". maski-proekt.media. Proekt. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ralph, Pat; Cranley, Ellen (7 December 2018). "Putin has 2, maybe 3, daughters he never talks about – here's everything we know about them". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 24 May 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Campbell, Matthew (26 May 2019). "Kremlin silent on reports Vladimir Putin and Alina Kabaeva, his 'secret first lady', have had twins". The Times. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "Timeline: Vladimir Putin – 20 tumultuous years as Russian President or PM". Reuters. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ↑ "Putin signs law allowing him to serve 2 more terms as Russia's president". www.cbsnews.com.

- ↑ "Putin — already Russia's longest leader since Stalin — signs law that may let him stay in power until 2036". USA TODAY.

- ↑ Guriev, Sergei; Tsyvinski, Aleh (2010). "Challenges Facing the Russian Economy after the Crisis". In Anders Åslund; Sergei Guriev; Andrew C. Kuchins (eds.). Russia After the Global Economic Crisis. Peterson Institute for International Economics; Centre for Strategic and International Studies; New Economic School. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-88132-497-6.

- ↑ "ПОСТУПЛЕНИЕ ИНОСТРАННЫХ ИНВЕСТИЦИЙ ПО ТИПАМ". Rosstat

- ↑ Putin: Russia's Choice, (Routledge 2007), by Richard Sakwa, Chapter 9.

- ↑ Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell In and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin, Yale University Press (2013), by Ben Judah, page 17.

- ↑ "It's Official: Sanctioned Russia Now Recession Free". Forbes. 3 April 2017.

- ↑ Frye, Timothy (2021). Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin's Russia. Princeton University Press. p. Template:Page?. ISBN 978-0-691-21246-3.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Gill, Graeme. "Building an Authoritarian Polity: Russia in Post-Soviet Times". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Reuter, Ora John (2017). The Origins of Dominant Parties: Building Authoritarian Institutions in Post-Soviet Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316761649. ISBN 978-1-316-76164-9.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Rosenberg, Matt (12 August 2016). "When Was St. Petersburg Known as Petrograd and Leningrad?". About.com. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ "Prime Minister of the Russian Federation – Biography". 14 May 2010. Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ "Putin says grandfather cooked for Stalin and Lenin". reuters.com. Reuters. 11 March 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ Sebestyen, Victor (2018), Lenin the Dictator, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, p. 422, ISBN 978-1-4746-0105-4

- ↑ "At Event, a Rare Look at Putin's Life". The New York Times. 27 January 2012.

- ↑ Vladimir Putin; Nataliya Gevorkyan; Natalya Timakova; Andrei Kolesnikov (2000). First Person. trans. Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. PublicAffairs. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-58648-018-9.

- ↑ First Person An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia's President Vladimir Putin The New York Times, 2000.

- ↑ Putin's Obscure Path From KGB to Kremlin Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 19 March 2000.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 (Sakwa 2008, p. 3)

- ↑ Sakwa, Richard. Putin Redux: Power and Contradiction in Contemporary Russia (2014), p. 2.

- ↑ "Prime Minister". Russia.rin.ru. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ Truscott, Peter (2005). Putin's Progress: A Biography of Russia's Enigmatic President, Vladimir Putin. p. 40. ISBN 9780743496070. Retrieved 25 February 2022 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "In Tel Aviv, Putin's German Teacher Recalls 'Disciplined' Student". Haaretz. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ↑ Hoffman, David (30 January 2000). "Putin's Career Rooted in Russia's KGB". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Lynch, Allen. Vladimir Putin and Russian Statecraft, p. 15 (Potomac Books 2011).

- ↑ Владимир Путин. От Первого Лица. Chapter 6 Archived 30 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Pribylovsky, Vladimir (2010). "Valdimir Putin" (PDF). Власть–2010 (60 биографий) (in русский). Moscow: Panorama. pp. 132–139. ISBN 978-5-94420-038-9.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin as a Spy Working Undercover from 1983". 30 June 1983. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ (Sakwa 2008, pp. 8–9)

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Hoffman, David (30 January 2000). "Putin's Career Rooted in Russia's KGB". The Washington Post. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ↑ Chris Hutchins (2012). Putin. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-78088-114-0.

But these were the honeymoon days and she was already expecting their first child when he was sent to Moscow for further training at the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute in September 1984 [...] At Red Banner, students were given a nom de guerre beginning with the same letter as their surname. Thus Comrade Putin became Comrade Platov.

- ↑ Andrew Jack (2005). Inside Putin's Russia: Can There Be Reform without Democracy?. Oxford University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-19-029336-9.

He returned to work in Leningrad's First Department for intelligence for four and a half years, and then attended the elite Andropov Red Banner Institute for intelligence training before his posting to the German Democratic Republic in 1985.

- ↑ Vladimir Putin; Nataliya Gevorkyan; Natalya Timakova; Andrei Kolesnikov (2000). First Person: An Astonishingly Frank Self-Portrait by Russia's President Vladimir Putin. Public Affairs. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7867-2327-0.

I worked there for about four and a half years, and then I went to Moscow for training at the Andropov Red Banner Institute, which is now the Academy of Foreign Intelligence.

- ↑ "Putin set to visit Dresden, the place of his work as a KGB spy, to tend relations with Germany". International Herald Tribune. 9 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Gessen, Masha (2012). The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (1st ed.). New York: Riverhead. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-59448-842-9. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Belton, Catherine (2020). "Did Vladimir Putin Support Anti-Western Terrorists as a Young KGB Officer?". POLITICO. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin, The Imperialist". Time. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Sakwa, Richard (2007). Putin : Russia's Choice (2nd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-415-40765-6. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ R. Sakwa Putin: Russia's Choice, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ R. Sakwa Putin: Russia's Choice, p. 11.

- ↑ Remick, David (3 August 2014). "Watching the Eclipse". The New Yorker. No. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ↑ Madslien, Jorn (4 July 2007). "Russia's economic might: spooky or soothing?". BBC News. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Arkhipov, Ilya (24 January 2013). "Putin Approval Rating Falls to Lowest Since 2000: Poll". Bloomberg. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ "Putin's Approval Rating Soars to 87%, Poll Says". The Moscow Times. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ↑ "The world's most popular politicians: Putin's approval rating hits 86%". Independent. 27 February 2015.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin's approval rating at record levels". The Guardian. 23 July 2015.

- ↑ Июльские рейтинги одобрения и доверия (in русский). Levada Centre. 23 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 January 2017. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ "Putin's approval ratings hit 89 percent, the highest they've ever been". The Washington Post. 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Economic Problems, Corruption Fail to Dent Putin's Image". gallup.com. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Quarter of Russians Think Living Standards Improved During Putin's Rule" (in русский). Oprosy.info. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ No wonder they like Putin by Norman Stone, 4 December 2007, The Times.

- ↑ "Economic Problems, Corruption Fail to Dent Putin's Image". gallup.com. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ "Alexei Navalny: Is Russia's Anti-Corruption Crusader Vladimir Putin's Kryptonite?". Newsweek. 17 April 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- ↑ "Одобрение органов власти" (in русский). Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ "Successful World Cup fails to halt slide in Vladimir Putin's popularity". The Guardian. 16 July 2018.

- ↑ "Trust in Putin Drops to 39% as Russians Face Later Retirement, Poll Says". Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ "Disquiet on the Home Front: Kremlin Propagandists Struggle to Contain the Fallout from Pension Reform and Local Elections". Disinfo Portal. 1 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ "Things are going wrong for Vladimir Putin". The Economist. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ↑ ""Левада-Центр": две трети россиян считают, что в проблемах страны виноват Путин". znak.com. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | 'Good Tsar, Bad Boyars': Popular Attitudes and Azerbaijan's Future". Refworld. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- ↑ Inc, TV Rain (18 January 2019). "Рейтинг доверия Путину достиг исторического минимума. Он упал вдвое с 2015 года". tvrain.ru. Retrieved 19 January 2019.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Russians' trust in Putin has plummeted. But that's not the Kremlin's only problem". The Washington Post. 2019.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Fokht, Elizaveta (20 June 2019). "Is Putin's popularity in decline?". Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ↑ "Record 20% of Russians Say They Would Like to Leave Russia". Gallup.com. 4 April 2019. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ↑ "How Putin and the Kremlin lost Russian youths". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Доверие политикам (1)". wciom.ru. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ "Доверие политикам (2)". wciom.ru. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ "Одобрение институтов власти и доверие политикам" (in русский). Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- ↑ Kolesnikov, Andrei (15 June 2020). "Why Putin's Rating Is at a Record Low". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ↑ "Москвичи рассказали, кого видят президентом. На первом месте Путин, потом Навальный". www.znak.com. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ↑ "What Vladimir Putin Is Up To in Ukraine". Time. 22 November 2021.

- ↑ "Trust fall The Kremlin plans to reboot Russia's mass vaccination campaign, but there are worries this will bring down Putin's ratings". Meduza. Retrieved 16 November 2021.

- ↑ "Акции протеста 12 июня" (in Russian). Levada Centre. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- ↑ "15 Years of Vladimir Putin: 15 Ways He Has Changed Russia and the World". The Guardian. 6 May 2015.

- ↑ Garry Kasparov (28 October 2015). "Garry Kasparov: How the United States and Its Western Allies Propped Up Putin". The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ "Hillary Clinton Describes Relationship With Putin: 'It's... interesting'". Politico. 17 January 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ↑ "Hillary Clinton: Putin is Arrogant and Tough". GPS with Fareed Zakaria. 27 July 2014. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "President Vladimir Putin on Sec. Hillary Clinton". CNN. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama attacks 'self-centered' Vladimir Putin". The Daily Telegraph. 7 September 2014. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ Henry Kissinger (5 March 2014). "How The Ukraine Crisis Ends". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Steve (9 October 2019). "Berlin Wall anniversary: The 'worst night of my life'". BBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Mikhail Gorbachev claims Vladimir Putin saved Russia from falling apart". International Business Times. 27 December 2014.

- ↑ Struck, Doug (5 December 2007). "Gorbachev Applauds Putin's Achievements". The Washington Post.

- ↑ "Decoding Vladimir Putin's Plan". U.S. News & World Report. 5 January 2015.

- ↑ State Building in Putin's Russia: Policing and Coercion after Communism p. 278, Brian D. Taylor. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- ↑ "Russia | Country report | Freedom in the World | 2005". freedomhouse.org. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ Diamond, Larry (7 January 2015). "Facing Up to the Democratic Recession". Journal of Democracy. 26 (1): 141–155. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0009. ISSN 1086-3214. S2CID 38581334.

- ↑ Levitsky, Steven; Way, Lucan A. (2010). Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49148-8.

- ↑ "Authoritarian Modernization in Russia: Ideas, Institutions, and Policies". Routledge.com. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ Gainous, Jason; Wagner, Kevin M.; Ziegler, Charles E. (2018). "Digital media and political opposition in authoritarian systems: Russia's 2011 and 2016 Duma elections". Democratization. 25 (2): 209–226. doi:10.1080/13510347.2017.1315566. ISSN 1351-0347. S2CID 152199313.

- ↑ Gelman, Vladimir (2015). Authoritarian Russia: Analyzing Post-Soviet Regime Changes. University of Pittsburgh Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt155jmv1. ISBN 978-0-8229-6368-4. JSTOR j.ctt155jmv1.

- ↑ Ross, Cameron (2018). "Regional elections in Russia: instruments of authoritarian legitimacy or instability?". Palgrave Communications. 4 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0137-1. ISSN 2055-1045.

- ↑ White, Stephen (2014). White, Stephen (ed.). Russia's Authoritarian Elections. doi:10.4324/9781315872100. ISBN 978-1-315-87210-0.

- ↑ Ross, Cameron (2011). "Regional Elections and Electoral Authoritarianism in Russia". Europe-Asia Studies. 63 (4): 641–661. doi:10.1080/09668136.2011.566428. ISSN 0966-8136. S2CID 154016379.

- ↑ Skovoroda, Rodion; Lankina, Tomila (2017). "Fabricating votes for Putin: new tests of fraud and electoral manipulations from Russia" (PDF). Post-Soviet Affairs. 33 (2): 100–123. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2016.1207988. ISSN 1060-586X. S2CID 54830119.

- ↑ Moser, Robert G.; White, Allison C. (2017). "Does electoral fraud spread? The expansion of electoral manipulation in Russia". Post-Soviet Affairs. 33 (2): 85–99. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2016.1153884. ISSN 1060-586X. S2CID 54037737.

- ↑ Bader, Max; Ham, Carolien van (2015). "What explains regional variation in election fraud? Evidence from Russia: a research note". Post-Soviet Affairs. 31 (6): 514–528. doi:10.1080/1060586X.2014.969023. ISSN 1060-586X. S2CID 154548875.

- ↑ "Russia Downgraded to 'Not Free' | Freedom House". freedomhouse.org. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ "Democracy Index 2015: Democracy in an age of anxiety" (PDF).

- ↑ Kekic, Laza. "Index of democracy by Economist Intelligence Unit" (PDF). The Economist. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- ↑ Diamond, Larry (1 January 2015). "Facing Up to the Democratic Recession". Journal of Democracy. 26 (1): 141–155. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0009. ISSN 1086-3214. S2CID 38581334.

- ↑ Bass, Sadie (5 August 2009). "Putin Bolsters Tough Guy Image With Shirtless Photos, Australian Broadcasting Corporation". ABC News. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Rawnsley, Adam (26 May 2011). "Pow! Zam! Nyet! 'Superputin' Battles Terrorists, Protesters in Online Comic". Wired. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ↑ "Putin gone wild: Russia abuzz over pics of shirtless leader". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Associated Press. 22 August 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ Kravchenko, Stepan; Biryukov, Andrey (13 March 2020). "Putin Doesn't Like Cult of Personality of Putin, Kremlin Says". Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ↑ Vladimir Putin diving discovery was staged, spokesman admits, The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- ↑ "Russians smell something fishy in Putin's latest stunt". Reuters. 29 July 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ Kavic, Boris; Novak, Marja; Gaunt, Jeremy (8 March 2016). "Slovenian comedian rocks with Putin parody; Trump to follow". Reuters. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ "A senile Putin becomes a parody of his own parody – The Spectator". The Spectator. 19 March 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

- ↑ "Let Putin be your fitness inspiration hero". The Guardian. 2015.

- ↑ Van Vugt, Mark (7 May 2014). "Does Putin Suffer From the Napoleon Complex?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ↑ "Statesmen and stature: how tall are our world leaders?". The Guardian. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- ↑ "Песни про Путина". Openspace.ru. 14 March 2008. Archived from the original on 18 September 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- ↑ Как используется бренд "Путин": зажигалки, икра, футболки, консервированный перец Gazeta 30 November 2007.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin's advisor found dead". CBS News. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ "Person of the Year 2007". Time. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ "Putin Answers Questions From Time Magazine". 20 December 2007. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Albright, Madeleine (23 April 2014). "Vladimir Putin – The Russian Leader Who Truly Tests The West". Time Magazine. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ Sharkov, Damien (20 April 2016). "Putin Is a 'Smart But Truly Evil Man,' says Madeleine Albright". Newsweek. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ↑ "The World's Most Powerful People 2016". Forbes. 14 December 2016.

For the fourth consecutive year, Forbes ranked Russian President Vladimir Putin as the world's most powerful person. From the motherland to Syria to the U.S. presidential elections, Russia's leader continues to get what he wants.

- ↑ Ewalt, David M. (8 May 2018). "The World's Most Powerful People 2018". Forbes. Retrieved 10 May 2018.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Sukhotsky, Cyril (5 March 2004), Путинизмы – "продуманный личный эпатаж"? [Putinism – "Thoughtful personal outrageous"?], BBC Russian (in русский), retrieved 29 January 2017

- ↑ Kharatyan, Kirill (25 December 2012), Кирилл Харатьян: Жаргон Владимира Путина [Vladimir Putin's Jargon], Ведомости (Vedomosti.ru) (in русский), retrieved 29 January 2017

- ↑ Sakwa, Richard (2007). Putin: Russia's Choice (2 ed.). Routledge. p. Template:Page?. ISBN 978-1-134-13345-1.

- ↑ Sonne, Paul; Miller, Greg (3 October 2021). Written at Moscow. "Secret money, swanky real estate and a Monte Carlo mystery". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ Harding, Luke (3 October 2021). Written at Monaco. "Pandora papers reveal hidden riches of Putin's inner circle". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ "Investigation Claims to Uncover Putin's Extramarital Daughter". The Moscow Times. 25 November 2020. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ Hoyle, Ben (14 March 2015). "Motherland is gripped by baby talk that Putin is father again". The Times. London. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 Sharkov, Damien (2 February 2016). "What Do We Know About Putin's Family?". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin and Google: The most popular search queries answered". BBC News. 19 March 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "A new Russian first Lady? Putin hints he may marry again". Reuters. 20 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 "Алина Кабаева после долгого перерыва вышла в свет, вызвав слухи о новой беременности (ФОТО, ВИДЕО)" [Alina Kabaeva after a long break was published, triggering rumors of a new pregnancy (PHOTO, VIDEO)]. NEWSru (in русский). 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "Russia President Vladimir Putin's divorce goes through". BBC News. 2 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Allen, Cooper (2 April 2014). "Putin divorce finalized, Kremlin says". USA Today. Archived from the original on 25 April 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ MacFarquahar, Neil (13 March 2015). "Putin Has Vanished, but Rumors Are Popping Up Everywhere". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 March 2015. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ Dettmer, Jamie (28 May 2019). "Reports of Putin Fathering Twins Test Free Speech in Russia". Voice of America. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Путин сообщил о рождении второго внука" [Putin announced the birth of a second grandson] (in русский). NTV. 15 June 2017. Archived from the original on 3 October 2021. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ Agence France-Presse (15 June 2017). "Russia's Putin opens up about grandchildren, appeals for family privacy during live TV show". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ Kroft, Steve (19 May 2019). "How the Danske Bank money-laundering scheme involving $230 billion unraveled". CBS News. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ↑ "OCCRP – The Russian Banks and Putin's Cousin". reportingproject.net. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ↑ Wile, Rob (23 January 2017). "Is Vladimir Putin Secretly the Richest Man in the World?". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ↑ "Quote.Rbc.Ru :: Аюмй Яюмйр-Оерепаспц – Юйжхх, Ярпсйрспю, Мнбнярх, Тхмюмяш". Quote.ru. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- ↑ ЦИК зарегистрировал список "ЕР" Rossiyskaya Gazeta N 4504 27 October 2007.

- ↑ ЦИК раскрыл доходы Путина Vzglyad. 26 October 2007.

- ↑ Radia, Kirit (8 June 2012). "Putin's Extravagant $700,000 Watch Collection". ABC News. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ Hanbury, Mary (23 June 2017). "How Vladimir Putin spends his mysterious fortune rumoured to be worth $70 billion". The Independent. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ Rickett, Oscar (17 September 2013). "Why Does Vladimir Putin Keep Giving His Watches Away to Peasants?". Vice. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ↑ "Is Vladimir Putin the richest man on earth?". News.com.au. 26 September 2013. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ Joyce, Kathleen (29 June 2019). "What is Russian President Vladimir Putin's net worth?". FOXBusiness. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ↑ Gennadi Timchenko: Russia's most low-profile billionaire Sobesednik No. 10, 7 March 2007.

- ↑ Harding, Luke (21 December 2007). "Putin, the Kremlin power struggle and the $40bn fortune". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 August 2008.

- ↑ Tayor, Adam. "Is Vladimir Putin hiding a $200 billion fortune? (And if so, does it matter?)". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ↑ William Echols (14 May 2019). "Are 'Putin's Billions' a Myth?". Polygraph.info. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ↑ Прямая линия с Владимиром Путиным состоится 14 апреля в 12 часов (in русский). Echo of Moscow. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Luke Harding (3 April 2016). "Revealed: the $2bn offshore trail that leads to Vladimir Putin". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Der Zirkel der Macht von Vladimir Putin, Süddeutsche Zeitung

- ↑ Wladimir Putin und seine Freunde, Süddeutsche Zeitung

- ↑ Revealed: the $2bn offshore trail that leads to Vladimir Putin, The Guardian

- ↑ "All Putin's Men: Secret Records Reveal Money Network Tied to Russian Leader". panamapapers.icij.org. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ "Panama Papers: Putin associates linked to 'money laundering'". BBC News. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Galeotti, Mark (4 April 2016). "The Panama Papers show how corruption really works in Russia". Vox Business and Finance. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ Harding, Luke (3 April 2016). "Sergei Roldugin, the cellist who holds the key to tracing Putin's hidden fortune". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ↑ Kasparov, Garry. "Starr Forum: The Trump-Putin Phenomenon". MIT Center for International Studies. MIT Center for International Studies. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ↑ Solovyova, Olga (5 March 2012). "Russian Leaders Not Swapping Residences". The Moscow Times, Russia. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ↑ "Тайна за семью заборами". Kommersant.ru. 31 January 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Elder, Miriam (28 August 2012). "Vladimir Putin 'Galley Slave' Lifestyle: Palaces, Planes and a $75,000 Toilet". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ↑ How the 1980s Explains Vladimir Putin. The Ozero group. By Fiona Hill & Clifford G. Gaddy, The Atlantic, 14 February 2013.

- ↑ Foreign, Our (3 March 2011). "'Putin Palace' Sells for US$350 Million". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ↑ "Putin's Palace? A Mystery Black Sea Mansion Fit for a Tsar". BBC. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ↑ Russia : Russia president Vladimir Putin rule : achievements, problems and future strategies. International Business Publications, USA. Washington, DC, USA: International Business Publications, USA. 2014. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4330-6774-7. OCLC 956347599.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ "Putin's spokesman dismisses report of palace on Black Sea". RIA Novosti. 23 December 2010.

- ↑ "Navalny Targets 'Billion-Dollar Putin Palace' in New Investigation". The Moscow Times. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ "ФБК опубликовал огромное расследование о "дворце Путина" в Геленджике. Вот главное из двухчасового фильма о строительстве ценой в 100 миллиардов". Meduza.io. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ "ФБК опубликовал расследование о "дворце Путина" размером с 39 княжеств Монако". tvrain.ru. 19 January 2021. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ↑ "Сколько собак у Путина?" [How many dogs does Putin have?]. aif.ru (in русский). 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ 183.0 183.1 Timothy J. Colton; Michael MacFaul (2003). Popular Choice and Managed Democracy: the Russian elections of 1999 and 2000. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution. p. Template:Page?. ISBN 978-0-8157-1535-1.

- ↑ Putin Q&A: Full Transcript Time. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- ↑ "Putin and the monk". FT Magazine. 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "The enduring grip of the men—and mindset—of the KGB". The Economist. 25 April 2020.

- ↑ "Putin to talk pipeline, attend football game". B92. 22 March 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ↑ "Bandy, how little known sport is winning converts". The Local. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Kremlin Biography of President Vladimir Putin". putin.kremlin.ru. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ "NPR News: Vladimir Putin: Transcript of Robert Siegel Interview". legacy.npr.org. 15 November 2001. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "Putin awarded eighth dan by international body". Reuters. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- ↑ "Black-Belt President Putin: A Man of Gentle Arts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016.

- ↑ Putin, Vladimir; Vasily Shestakov; Alexey Levitsky (2004). Judo: History, Theory, Practice. Blue Snake Books. p. Template:Page?. ISBN 978-1-55643-445-7.

- ↑ Hawkins, Derek (18 July 2017). "Is Vladimir Putin a judo fraud?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "I'll Fight Putin Any Time, Any Place He Can't Have Me Arrested". Lawfare. 21 October 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Вьетнам: Наш президент круче американского. Путину – орден Хо Ши Мина. Нас там пока любят (in русский). Аргументы и Факты. 7 March 2001.

- ↑ Первый Президент Республики Казахстан Нурсултан Назарбаев Хроника деятельности 2004 год (PDF) (in русский). Astana. 2009. p. 15. ISBN 978-601-80044-3-8.

Президент также подписал указы "О награждении орденом "Алтын ыран" (Золотой орел) Путина В.В."...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Chirac décore Poutine". Vidéo Dailymotion. 13 October 2006.

- ↑ "CSTO: SAFE CHOICE IN CENTRAL ASIA". Eurasia Daily Monitor. 4 (191). 2007.

- ↑ Atul Aneja Putin goes calling on the Saudis. The Hindu. 20 February 2007.

- ↑ Putin Receives Top UAE's Decoration, Order of Zayed Archived 25 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Rbc.ru, 10 September 2007.

- ↑ Sanchez, Fabiola (2 April 2010). "Russia offers Venezuela nuclear help, Chavez says". The Seattle Times.

- ↑ "Ordonnance Souveraine n° 4.504 du 4 octobre 2013 portant élévation dans l'Ordre de Saint-Charles" (in français). Journal de Monaco. 4 October 2013.

- ↑ "Raul Castro Welcomes Russian President Vladimir Putin". Escambray. 11 July 2014.

- ↑ "Putin receives Serbia's top state decoration". B92. 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Putin becomes first foreign leader to get China's Order of Friendship". TASS. 1 January 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ INFORM.KZ (28 May 2019). "Nursultan Nazarbayev awards Order of Yelbasy to Vladimir Putin". inform.kz.

- ↑ "The Academic Council of Baku Slavic University at its meeting held on January 8, 2001 by the unanimous decision awarded the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin the title of BSU Honorary Doctor for his service in extending and strengthening scientific, economic and social relations between Azerbaijan and the Russian Federation". 8 January 2001.

- ↑ "Putin Concludes Visit to Armenia Lays Wreath at Genocide Monument". Asbarez. 17 September 2001.

- ↑ "Putin receives honorary doctorate from Athens University". Athens News Agency. 7 December 2001.

- ↑ "B92 News: Belgrade University to award Putin honorary doctorate". Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- ↑ "Alexy II is awarded the highest Muslim Order". Interfax-Religion. 4 July 2006.

- ↑ Орден Шейх-уль-ислама (in русский). Управление Мусульман Кавказа. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin awarded the Serbian Orthodox Church's highest distinction | Serbian Orthodox Church [Official web site]". spc.rs. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ↑ "Vladimir Putin in China Confucius Peace Prize fiasco". BBC. 15 November 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ Wong, Edward (15 November 2011). "In China, Confucius Prize Awarded to Putin". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ "Pope Francis meets Putin for a diplomatically difficult talk". Religion News Service. 10 June 2015.

- ↑ "Vatican says Pope meant no offense calling Abbas 'angel of peace'". Reuters. 19 May 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2016.

- ↑ "Person of the Year 2007". Time. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ↑ "Глобальный игрок. Expert magazine. 48 (589) 24 December 2007". Expert.ru. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Nemenov, Alexander (24 September 2019). "The memories Chechnya hold". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ↑ Liotta, Paul (7 October 2015). "On his birthday, 7 things you might not know about Russian president Vladimir Putin". New York Daily News. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

Further reading[edit]

- Lourie, Richard (2017). Putin: His Downfall and Russia's Coming Crash. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-53808-8.

- Arutunyan, Anna (2015) [2012; Czech ed.]. The Putin Mystique: Inside Russia's Power Cult. Northampton, MA: Olive Branch Press. ISBN 978-1-56656-990-3. OCLC 881654740.

- Asmus, Ronald (2010). A Little War that Shook the World: Georgia, Russia, and the Future of the West. NYU. ISBN 978-0-230-61773-5.

- Frye, Timothy. 2021. Weak Strongman: The Limits of Power in Putin's Russia. Princeton University Press.

- Gessen, Masha (2012). The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. London: Granta. ISBN 978-1-84708-149-0.

- Judah, Ben (2015). Fragile Empire: How Russia Fell in and Out of Love with Vladimir Putin. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20522-0.

- Lipman, Maria. "How Putin Silences Dissent: Inside the Kremlin's Crackdown." Foreign Affairs 95#1 (2016): 38+.

- Myers, Steven Lee. The New Tsar: The Rise and Reign of Vladimir Putin (2015).

- Naylor, Aliide. The Shadow in the East: Vladimir Putin and the New Baltic Front (I.B. Tauris, 2020), 256 pp.

- Rosefielde, Steven. Putin's Russia: Economy, Defence and Foreign Policy (2020) excerpt

- Sakwa, Richard. The Putin Paradox (Bloomsbury, 2020) online.

- Sakwa, Richard. Putin Redux: Power and Contradiction in Contemporary Russia (2014). online review

- Sperling, Valerie. Sex, Politics, & Putin: Political Legitimacy in Russia (Oxford UP, 2015). 360 pp.

- Stoner, Kathryn E. 2021. Russia Resurrected: Its Power and Purpose in a New Global Order. Oxford University Press.

- Toal, Gerard. Near Abroad: Putin, the West, and the Contest Over Ukraine and the Caucasus (Oxford UP, 2017).

External links[edit]

- CS1 errors: generic name

- Vladimir Putin

- 20th-century Eastern Orthodox Christians

- 20th-century presidents of Russia

- 20th-century Russian politicians

- 21st-century Eastern Orthodox Christians

- 21st-century presidents of Russia

- 21st-century Russian politicians

- 1952 births

- 2003 Tuzla Island conflict

- Acting presidents of Russia

- Candidates in the 2000 Russian presidential election

- Candidates in the 2004 Russian presidential election

- Candidates in the 2012 Russian presidential election

- Candidates in the 2018 Russian presidential election

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- Directors of the Federal Security Service

- Federal Security Service officers

- Grand Croix of the Légion d'honneur

- Grand Crosses of the Order of St. Sava

- Heads of government of the Russian Federation

- Independent politicians in Russia

- KGB officers

- Kyokushin kaikan practitioners

- Living people

- Our Home – Russia politicians

- People from Saint Petersburg

- People involved in plagiarism controversies

- People of the annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

- People of the Chechen wars

- People of the Russo-Georgian War

- People of the Syrian civil war

- Presidents of Russia

- Recipients of the Order of Ho Chi Minh

- Recipients of the Order of Saint-Charles

- Recipients of the Order of St. Sava

- Russian male judoka

- Russian male karateka

- Russian Orthodox Christians from Russia

- Russian sambo practitioners

- Saint Petersburg State University alumni

- Time Person of the Year

- United Russia politicians

- United Russia presidential nominees

- Russian nationalists

- Conservatism in Russia

- Russian individuals subject to the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctions

- Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons List